Test Data Capture and Data

Analysis Software

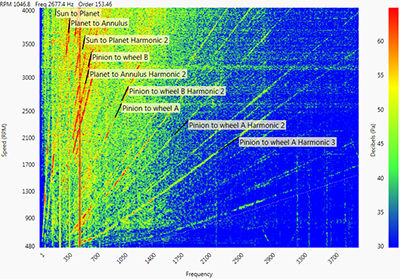

For gear whine issues typical measurements

considered include noise measurements

via microphones, casing

vibration measurements via accelerometers,

and transmission error measurements

via angular encoders.

Measurements of gear whine should

include tests performed in-vehicle that

capture the full operating range through,

for example, vehicle accelerations at different

throttle levels and vehicle coastdown.

Further dyno rig tests should be

performed to isolate and understand

transmission and driveline noise sources.

Care must be taken in correlating any

rig test results with those of vehicle tests

and the original subjective noise problem.

Different boundary conditions on

the rig, as compared to in-vehicle, can

significantly change the dynamics of the

system and subsequent frequency content

of problem areas (Ref. 4).

Accurate data acquisition requires

calibrated microphones and accelerometers and high-fidelity data logging.

Further, an accurate speed signal

is required for analysis of component

orders. Measurement data can be captured

and analyzed using MEASA data

capture and analysis software. Data analysis

tools allow the user to process the

data in a number of ways. By linking to a

model of the transmission system under

consideration, potential excitation orders

and the components and harmonics to

which they correspond may be imported

into the data analysis tools to allow easy

identification of the main contributions

to specific orders and to the total noise/

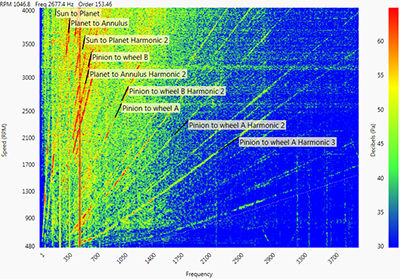

vibration content. Critical plots given

include waterfall plots and order cuts

giving quantitative results for the noise

due to specific sources and their prominence

with respect to total noise (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Measured noise displayed as a waterfall plot with

excitation orders automatically labelled via data from

a system simulation model.

- Click image to Enlarge

Although less common than noise

and vibration measurements, the source

of gear whine — loaded transmission

error — can also be measured using

angular encoders. For a transmission

or driveline system on a test rig, encoders

may be placed on the input and output

shafts in order to measure the whole

gearbox, or may be placed straddling

a sub-system to measure just that subsystem.

As with noise and vibration test

results, TE test results may be captured

and analyzed using MEASA. Fourier

analysis can be performed to identify the

contributions from different stages and

angular TE values can be converted to

linear via the base radius values for the

gears. A link to a model of the system

allows import of gear mesh orders and

their harmonics for easy identification

within the data analysis tool.

Using these measurement and data

analysis techniques, the nature of the

noise issue can be quantified and the

contributions from the potential excitations

in the transmission identified. But

how can design changes be made, their

effect on the problem assessed,

and solutions found efficiently

and cost-effectively? This is

the role of advanced transmission

and driveline simulation

software within

the troubleshooting

methodology.

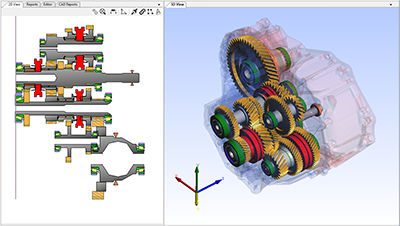

Full System Simulation

Once a gear whine issue has been identified

and the contributions clarified via

measurement and data analysis techniques,

simulation software plays a vital

role in efficiently assessing potential

solutions. As gear whine is a system-level

issue, where solutions may be considered

from gear macro geometry design, gear

microgeometry design, system stiffness

and mass properties and the transmissibility

of TE to the casing, state of the art

system-level software is required to be

able to perform various analyses of interest.

Design changes need to be assessed

effectively — not just for their effect on

the noise problem at hand — but also for

other considerations of importance in

the design process so as, for example, not

to compromise durability.

Such durability, loaded tooth contact

and dynamic response analyses may be

performed using standalone commercial

FE packages. However, this approach is

problematic as it requires models with

different levels of fidelity to calculate

each aspect. What’s more, models are

very difficult to set up and do not lend

themselves well to analyzing the effects

of design changes easily and quickly. On

the other hand, integrated CAE software

such as MASTA provides tools

for engineers to perform these analyses

using a single model and parameter

set. And, model generation is rapid and

provides the flexibility to make complex

design changes on the fly, seeing immediate

results within a seamless workflow.

Analyses are fast enough to enable

parameter space DOE studies, including

assessing the robustness of any design

changes to the expected variability in

actual parts due to manufacturing and

assembly tolerances.

A range of analyses relevant for gear

whine problems can be performed on

the system-level model. To

begin, a number of static

analyses are usually performed

covering the operating

range to calculate

deflections of the system,

including misalignments

at gear meshes, and

durability results for components.

Baseline durability results

should be obtained and compared with

results when design changes are made to check that no compromise in durability

is introduced. The system deflection

model consists of an FE-based

model where shafts are considered as

Timoshenko beam elements; bearings

are represented via a bespoke non-linear

contact formalism, taking into account

the full geometry details; clearances, preloads,

etc., gear meshes are represented

as bespoke non-linear contact models;

and housings and complex asymmetric

shafts are included via stiffness and mass

matrices obtained via dynamic reduction

from a full FE model of the geometry.

Durability results for bearings, gears,

shafts and other coupling components

are obtained by passing deflections and

loads from the analysis results to implementations

of the relevant international

standards (Refs. 5–7).

Although it should be noted that the

solution to gear whine does not always

lie in optimizing gear microgeometry,

this is often the first area of investigation

due to its relative ease. Further, if

late in the development process, this is

often the easiest option to implement

due to the minimal change to manufacturing

processes and tooling required.

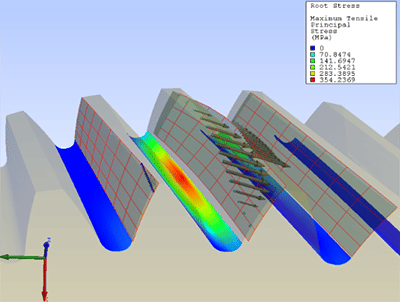

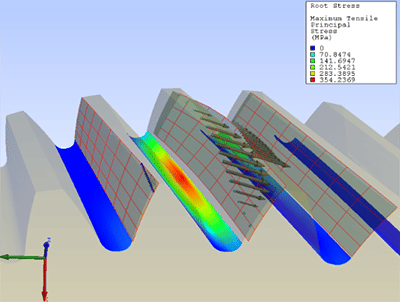

Calculation of TE can be performed

using a loaded tooth contact analysis

(LTCA). Torque, misalignment, gear

macro and microgeometry are used as

inputs. It is very important to use an

accurate LTCA in order to get an accurate

calculation of TE. A hybrid FE and

Hertzian, contact-based formalism are

used to accurately capture the stiffness

at each contact location while providing

a fast calculation suitable for assessing

microgeometry parameter changes and

robustness to tolerances (Fig. 4). Such

a calculation is comparable in accuracy

to a full FE contact analysis while being

many orders of magnitude faster. An FE

model of the gear macro geometry is

built automatically in the software and

used to obtain the overall bending and

base rotation stiffness of the gear teeth,

with consideration made for coupling

between teeth. This bending stiffness

is combined with a Hertzian line contact

formalism to calculate the overall

stiffness of any potential contact points.

Potential contact lines are split into

strips and force balance and compatibility

conditions are formulated and solved

(Ref. 8) to calculate the load distribution

across the mesh and the transmission

error for the input torque. This LTCA

can be used to optimize gear microgeometry

and macro geometry for minimal

transmission error. Consideration

must be given to the entire operating

range of loads and the robustness of the

proposed design to variation in load and

misalignments, as well as variation in

gear microgeometry within the manufacturable

tolerance range.

Figure 4 Hybrid FE and Hertzian-based

loaded tooth contact analysis.

- Click image to Enlarge

It is often assumed in the analysis

workflow described above that the

deflections of the system affect the tooth

contact — but the tooth contact conditions

do not affect the deflections of

the system. Hence, as above, a calculation

of misalignments is first performed

using a static system-level model, and

these misalignments, assumed constant

throughout the mesh cycle, are used as

inputs into the tooth contact calculation.

This assumption is often — but not

always — valid. In a number of important

cases, such as the tooth contact

conditions of a planet gear, the interaction

between the two meshes of the

planet means that the system deflection

and tooth contact conditions need to

be solved in a coupled calculation. In

such a calculation the assumption of a

fixed misalignment throughout the mesh

cycle is removed and the variation in

misalignment is calculated. Further, for

planetary systems where contact conditions

may vary, as the planet carrier

rotates, such a coupled calculation

is required. The software solutions discussed

here also provide such a calculation.

Tooth contact analysis results can

often provide good validation that the

analysis model is set up and performing

correctly. A contact patch test is a

relatively easy and common test to perform

and contact patch test results can

be compared directly against analysis

results (Fig. 5). If correlation is good,

this gives confidence in the analysis

model, implying that calculated misalignments,

microgeometry inputs, and

calculated load distribution under the

tested loads are accurate. Further, if TE

measurements have been performed,

measured and calculated, TE can be

directly compared.

Figure 5 Measured and simulated loaded contact patterns.

- Click image to Enlarge

Analysis of the dynamics of the system

can be performed via modal and harmonic

response analyses. For a modal

analysis of the system at a given input

load, a linearized model of the non-linear

static analysis model at that load is

automatically built. The natural frequencies

and corresponding mode shapes

can therefore be calculated for different

operating loads. Campbell diagrams

can be used to identify potential excitations

of the system where, for example,

gear mesh frequencies or their harmonics

cross the natural frequencies of the

system. Further, the energy content of

the mode shapes can be visualized and

investigated to identify the main contributing

components to those potential

resonances (Fig. 6). A target would

be to minimize the number of natural

frequencies within the operating range while also separating any way

in which do lie within the range

from each other.

Figure 6 Mode shape and kinetic energy content of

system mode at 701 Hz.

- Click image to Enlarge

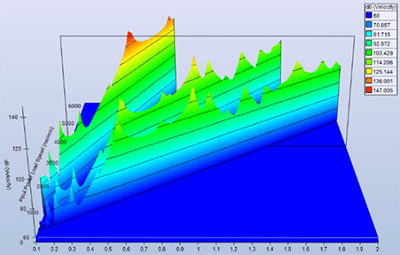

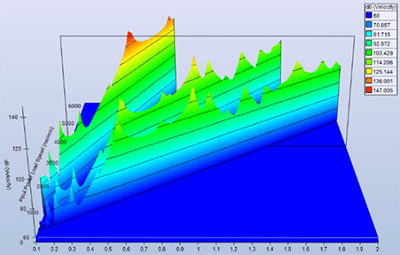

The method of calculation of

the system response to the transmission

error introduced by

Steyer et al (Ref.9) can be used to

calculate the casing acceleration

at virtual accelerometer locations.

As the excitation is periodic

and the stiffness around the

loaded condition can be considered

linear, the calculation can

be performed very quickly in the

frequency domain. Static transmission

error is the assumed excitation

input of the system and the first step

is to calculate the dynamic force at the

gear meshes, which leads to a relative

displacement at the mesh given by this

transmission error. This force is known

as the dynamic mesh force that is calculated

from the dynamic compliances

at each side of the gear meshes. The

dynamic mesh force is then applied as

an excitation to the system model to calculate

the response at any point on the

system to this excitation. Waterfall charts

can be plotted of dynamic response for

any point on the model (Fig. 7) and

compared with accelerometer and/or

microphone data obtained via noise and

vibration tests.

Figure 7 Calculated casing response to

excitation by transmission error.

- Click image to Enlarge

Once a virtual model is correlated

with test data, contributing modes to

problem frequencies can be identified

via the waterfall charts and natural frequencies.

Then, the contributing components

to those modes can be identified

with mode shapes and energy contributions.

With the results obtained,

the design of these components can

be adjusted to improve the dynamic

response of the analysis model. Once the

desired results are obtained, the design

changes can be implemented on a prototype

and tested again to confirm the

expected improvements.

Benefits of an Integrated Software

Approach to Troubleshooting Gear

Whine

- Reduced product development time

by targeting solutions in a virtual testing

environment.

- Reduced product development cost by

minimizing component testing.

- Allows production variation to be

investigated and minimized prior to

product launch.

Summary

The development cycle of transmission

systems is a complex and costly process.

With increased demands for lower-

noise transmissions and drivelines

driven by markets such as EV and HEVs,

more pressure is being placed on designers

to design for low noise and for analysts

to solve known gear whine issues

quickly and efficiently. Quick solutions

with minimal cost can be found with

a combination of solid methodology,

experience and the right software tools.

Software plays a vital role within this

process. Assessing, controlling and finetuning

designs for gear whine within

an integrated CAE environment, such

as that offered by SMT, where test data

capture and data analysis, together with

advanced simulation methods, are seamlessly

integrated, provides engineers with

the flexibility and freedom to achieve

new levels of quality otherwise too costly

and time-consuming to achieve through

physical prototyping alone.

References

- Smith, J.D. Gear Noise and Vibration, Second

Edition, Marcel Dekker, Inc. 2003.

2. D. R. Houser, D.R. et al. “Determining the

Source of Gear Whine Noise,” Gear Solutions,

February 2004.

- www.smartmt.com/masta.

- Meinhardt, G. et al. “Correlation of Axle

End-of-Line (EOL) NVH Performance and

Laboratory Dynamometer Performance,” SAE

2005 Noise and Vibration Conference, 005-01-

2306.

- BS ISO 6336-2: 2006(E). Calculation of Load

Capacity of Spur and Helical Gears — Part 2:

Calculation of Surface Durability (Pitting), 2006.

- BS ISO 6336-3: 2006(E).Calculation of Load

Capacity of Spur and Helical Gears — Part 3:

Calculation of Tooth Bending Strength, 2006.

- ISO/TS 16281: 2008(E). Rolling Bearings:

Methods for Calculating the Modified Reference

Rating Life for Universally Loaded Bearings,

2008.

- Conry, T.F. and A. Seireg. “A Mathematical

Programming Method for Design of Elastic

Bodies in Contact,” J.A.M. ASME, 2, 1971

- Chung, C. and G. Steyer et al. “Gear Noise

Reduction Through Transmission Error Control

and Gear Blank Dynamic Tuning,” SAE Noise

and Vibration Conference 1999-01-1766.

About Author

Dr. Paul Langlois is

CAE products development

department manager at

Smart Manufacturing

Technology Ltd. (SMT).

Having worked for SMT for

10 years, he has extensive

knowledge of transmission

analysis methods and their software

implementation. He manages the development

of SMT’s software products and was a main

contributor to many aspects of the technical

software development, such as MASTA’s

gear-loaded tooth contact analysis and NVH

functionality.