Among other calculation results,

RIKOR calculates the load distribution.

For the integrated bearing calculation in

RIKOR, the geometrical data of the bearings

are used (e.g., ball diameter, angle of

taper, etc.). The load distribution between

the rolling elements and race way in the

bearing is calculated. Then the data are

provided for other calculations, such as

the mesh calculation used in this project.

Comparison of mesh excitation for

designed and measured microgeometry

— determination of microgeometry.

The microgeometry is one of the most

important influence parameters on vibration

excitation of gears. Therefore it is

necessary to model gear microgeometry

as accurately as possible. Since the

designed microgeometry is often not

sufficient, the microgeometry has to be

measured topologically. All teeth on both

flanks were measured topologically with

30 points in face width direction and 30

points in tooth profile direction using a

Klingelnberg P40 measuring center. This

topological data was converted for use

as microgeometry in the calculation program.

Figure 2 shows the designed microgeometry

of the two examined drive gears.

In Figure 3 the averaged microgeometry

of the examined drive gear from topological

measurement in the whole field

of action is shown. There are some differences

between the designed microgeometry

and the measured microgeometry

— which could influence the excitation.

Since the deviation of individual

teeth is even greater than the averaged

microgeometry, the influence on excitation

can be increased additionally.

Figure 2 Nominal microgeometry of counter drive gear.

- Click image to enlarge

Figure 3 Measured microgeometry of counter drive gear.

- Click image to enlarge

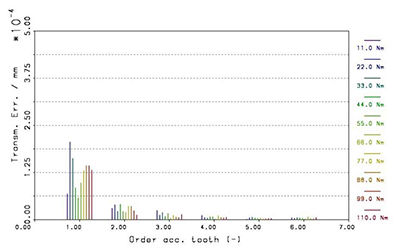

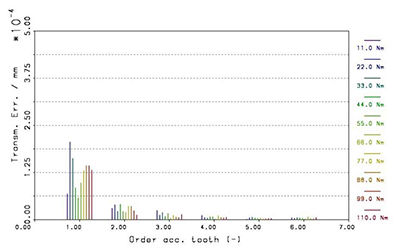

Transmission error. The calculation

of transmission error has been done for

both designed and measured microgeometry;

the time-dependent curves were

transformed into the frequency domain.

In the generated spectra the exciting

characteristics of the mesh could

be analyzed properly. In Figures 4 and 5 the results are shown for the design

microgeometry.

Figure 4 Transmission error with the designed microgeometry for gearbox A counter drive

stage at different load.

- Click image to enlarge

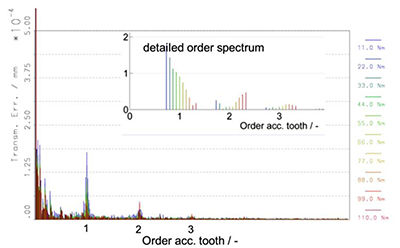

Figure 5 Transmission error with the designed microgeometry for gearbox B counter drivestage

at different load.

- Click image to enlarge

Both gearboxes show

comparable exciting characteristics. The

amplitudes of transmission error are

very low level from 0.03 μm to 0.2 μm

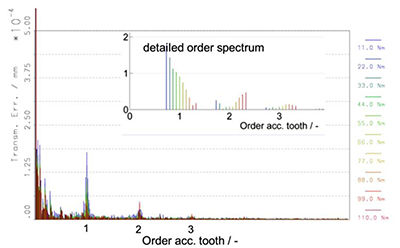

for 1st order. The results of the transmission

error calculation with measured

microgeometry are shown in Figures

6 and 7; the calculation was done with

the individual measured flank geometry

for each tooth (no averaging). Because

every tooth is different in this calculation,

more orders are visible — not only

integer orders. Therefore in the pictures

of full order spectra (Figs. 6 and 7)

there is shown only the shape of amplitudes,

but no development of amplitudes

of TE with increasing load (different

colors). For this reason the details

of the spectra are displayed in Figures

6 and 7.

Figure 6 Transmission error with the measured microgeometry for gearbox A counter drivestage

at different load.

- Click image to enlarge

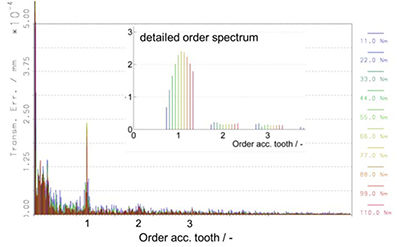

Figure 7 Transmission error with the measured microgeometry for gearbox B counter drivestage

at different load.

- Click image to enlarge

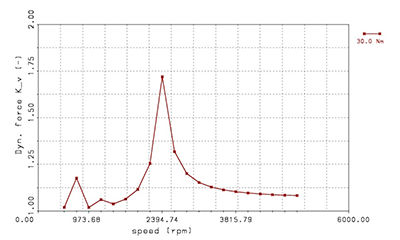

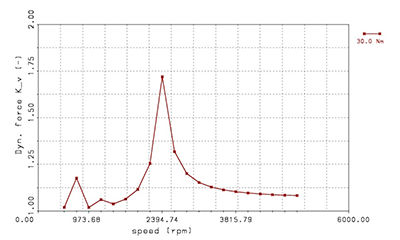

Figure 8 Resonance curve with designed microgeometry for gearbox A.

- Click image to enlarge

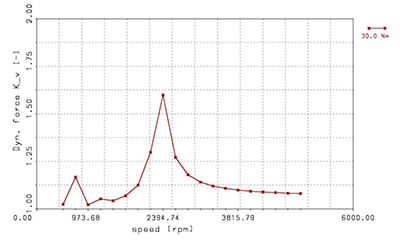

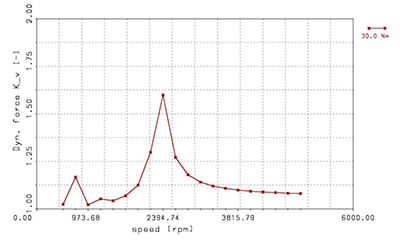

Figure 9 Resonance curve with designed microgeometry for gearbox B.

- Click image to enlarge

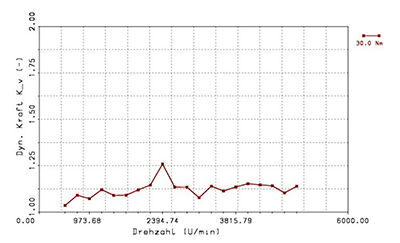

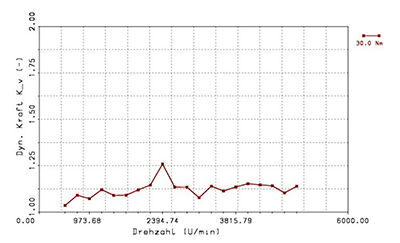

Figure 10 Resonance curve with measured microgeometry for gearbox A.

- Click image to enlarge

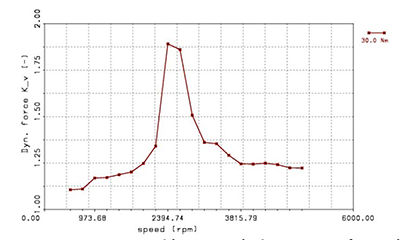

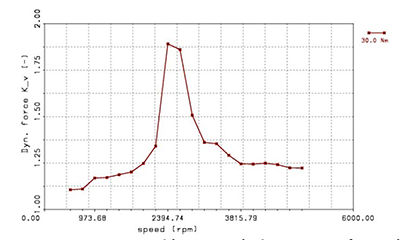

Figure 11 Resonance curve with measured microgeometry for gearbox B.

- Click image to enlarge

When comparing the transmission

error with designed microgeometry

and measured microgeometry,

there are different statements between

the gearbox A and B. Regarding gearbox

A, the excitation of tooth order and

its harmonics decreases down to 50%

of the amplitudes at design microgeometry

for high loads (see Figs. 4 and 6

details). Regarding gearbox B the excitation

of tooth order and its harmonics

increases to 150% of the amplitudes of

design microgeometry (see Figs. 5 and 7

details). The amplitudes of transmission

error with amounts of around 0.1 μm

are very small and the manufacturing

of the real gears will change the transmission

error only by 0.1 μm to 0.2 μm.

But in analyzing lower frequency excitation

there can be seen some additional

excitation due to manufacturing errors.

This additional excitation at low frequencies

is typical for calculation with

measured microgeometry data. In this

case the amplitudes of mesh excitation

for very low order increase up to 3 times

the value of 1st order of mesh excitation,

and even the 0.3 mesh order gets an

amount of 2 times 1st order amplitude.

This effect leads to the assumption that

manufacturing errors probably have significant

influence on excitation and will

excite some frequencies that are not in

tooth frequency.

Dynamic tooth force. Since the geometry

of shafts for gearbox A and B are

very similar, it is possible to perform

dynamic calculations for both with the same dynamic model. It consists of eight

rotational degrees-of-freedom. The gear

mesh stiffness is calculated internally by

DZP (Ref. 4) for every integration step.

For comparison, the resonance curves of

dynamic tooth force factor Kv have been

calculated. The dynamic tooth force factor

Kv with measured microgeometry for

gearbox A is clearly lower at resonance

frequency (2,400 rpm) than Kv with the

designed microgeometry. Looking at

gearbox B, the dynamic tooth force factor

at resonance frequency is higher for the

calculation with measured microgeometry

in comparison to the calculation with

nominal microgeometry; these results

match the transmission error results.

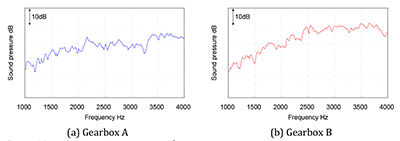

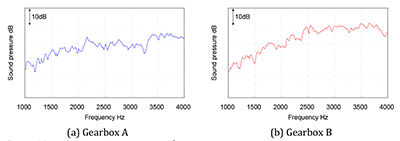

Figure 12 Noise measurement result.

- Click image to enlarge

All in all, calculation with design

microgeometry shows comparable

noise excitation of gearbox A and B. But

regarding measured microgeometry,

noise excitation of gearbox B is higher

than noise excitation of gearbox A.

Noise measurement results. In the production

facility, 100 gearboxes have been

tested on their airborne noise behavior.

Then the gearbox with the highest

noise level was measured on the same test

bench. The result of each type is shown

in Figure 12. Gearbox A (Fig. 12(a)) has

a broad frequency range of high noise

behavior between 2,000 Hz and 2,500 Hz.

For the gearbox B (Fig. 12(b)) there is

shown a constant increasing noise behavior

with higher frequency. Comparing the

curves, the noise of gearbox B is ultimately

higher than in gearbox A. This could

be reproduced by calculations with the

presented calculational method with the

program DZP (Ref. 4). It can be shown

that highly optimized design needs much

effort in manufacturing because small

deviations may have a big impact on

noise excitation.

Conclusion

In this paper a method for gear noise

prediction is presented. This method is

used in a comparison between the measurement

and calculation of gear noise

excitation for two automotive gearboxes.

After modelling the gear meshes with

their nominal main and microgeometry,

transmission error and dynamic tooth

force were calculated. In the first step the

mesh excitation of nominal and topologically

measured microgeometry was compared.

As a result the difference between nominal and measured microgeometry

had a significant impact on the excitation

behavior. In particular, highly optimized

microgeometry design needs much effort

in manufacturing because small deviations

in manufacturing may result in

major changes in noise excitation; noise

measurement results confirmed the

calculation. Additionally, the dynamic

behavior of shafts, bearings and housing

was addressed. The presented methodology

enables the gear engineer to optimize

the microgeometry of gears with respect

to their robust manufacturing

References

- Cooley, C., R. Parker and S. Vijayakar. “An

Efficient Finite Element Solution for Gear

Dynamics,” In: IOP Conf. Series: Materials

Science and Engineering, DOI:10.1088/1757-

899x/10/1/012150, 2010.

- Davoli, P., C. Gorla, F. Rossa, F. Rossi and G.

Boni. “Transmission Error and Noise Excitation

of Spur Gears,” In: Proceedings of the ASME

2007 10th International Power Transnmisson and

Gearing Conference, Las Vegas-DETC2007-34099,

2007.

- Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik E.V. (FVA)

(Hrsg.): FVA-Heft Nr. 914: Ritzelkorrektur (Rikor),

Version I. Rikor I, 2009.

- Forschungsvereinigung Antriebstechnik E.V. (FVA)

(Hrsg.): FVA-Heft Nr. 937: DZP, Version 5.0 und

DZPopt, Version 2.0, 2010.

- Heider, M. “Schwingungsverhalten von

Zahnradgetrieben,” TU München, Diss. 2012.

- Gerber, H. “Innere Dynamische Zusatzkräfte bei

Stirnradgetrieben,” TU München, Diss., 1984.

- Schmidt, G. “Berechnung der Wälzpressung

Schrägverzahnter Stirnräder unter

Berücksichtigung der Lastverteilung,” TU

München, Diss., 1973.

- Velex, P., J. Bruyère and D.R. Houser.

“Some Analytical Results on Transmission

Errors in Narrow-Faced Spur and Helical

Gears — Influence of Profile Modifications,”

Journal of Mechanical Design, Vol. 133, No. 3,

(March 2011), p. 11, ISSN: 1050-0472.

- Weber, C. and K. Banaschek. “Formänderung

und Profilrücknahme bei Gerad und

Schrägverzahnten Rädern,” Bd. 11, Schriftenreihe

Antriebstechnik, Braunschweig: Vieweg Verlag,

1955.