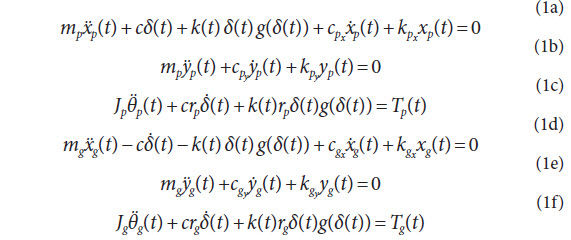

and gear mesh contact loss is mathematically induced by the

unit step function, g(δ(t)). The unit step function, g(δ(t)) = 0,

if δ(t) < 0 and g(δ(t)) = 1, if δ(t) ≥ 0. An over-dot means a time

derivative of the corresponding variable in the equations of

motion. In Equation 2 e(t) is the time-varying transmission

error function that represents the motion errors caused by

gear mesh deflections due to load and also due to manufacturing

deviations. Transmission error is a periodic function and

is simulated via discrete Fourier series amplitude and phase

of this periodic function in modeling schemes that exist in literature

(Refs. 16–17). The model can employ the transmission

error function either in a time-series form or in a broad-band frequency domain form from a measured or a simulated timeseries.

In other words, this model makes it possible to use measured

time-domain or broad-band frequency domain representation

of the long-period quasi-static transmission error to

predict dynamic transmission errors and dynamic mesh forces.

Moreover, the dynamic model developed in this study accepts

measured transmission error signal with any resolution, automatically

synchronizing the time resolution of the transmission

error signal with the time resolution of the dynamic model

equations for the right solution. A simplified mathematical representation

of such a signal in the time domain can be given as:

This transmission error function assumes an infinite number

of harmonics, sub-harmonics and overtones of the mesh frequency

ωm that are superimposed to obtain a broadband transmission

error function as in Equation 3. The quasi-static transmission

error, e(t), when measured from a gear set with indexing

errors, is periodic over the complete rotation of the gears in

mesh if the gears are unity-ratio gears. If two gears with different

number of teeth are used, then transmission error signal is

periodic over Z1Z2 rotations of both gears, where Z1 and Z2 represent

the number of teeth on the pinion and the gear, respectively.

On the contrary, for a gear set with no indexing errors,

transmission error is periodic over a mesh cycle and over a complete

rotation of the gear. This difference constitutes the main

mechanism for the signals to convolute.

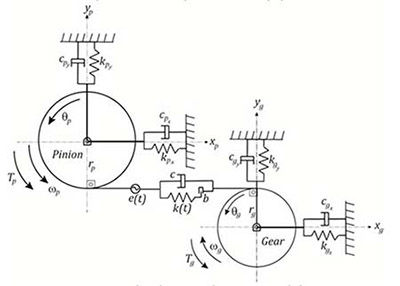

This dynamic model employs a number of assumptions. First

of all, gear wheels are assumed to be rigid, with flexibility only

coming from the gear mesh. Gear motions in some other directions,

such as rotations about x and y, and translations in z, are

excluded for the sake of simplicity. Bearings are assumed to be

linear. Finally, simplified damping elements are used. The model

presented here makes use of Rayleigh damping, where [C] = α

[M] + β [K]. Here, [C], [M] and [K] represent the overall system

damping, mass and stiffness matrices and αand β are constant

coefficients, and α = 479 and β = 1.4·10-7 was used here.

Experimental Transmission Error Measurements

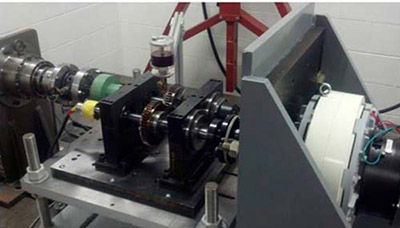

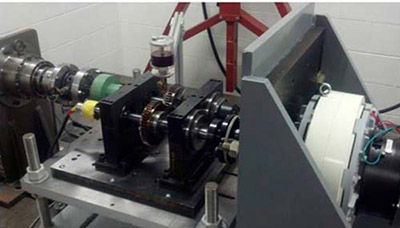

Test machine and set-up. In this study, an open-architecture

gearbox with drive and load capacity was used to measure the

quasi-static transmission error of spur gears with different

indexing errors. This rig (Fig. 2) is designed to operate gears

under high-load and low-speed (loaded quasi-static) conditions.

A small DC motor is connected to a 100:1 ratio harmonic drive

to reduce the speed significantly while increasing the torque

delivered to the gear pair. The harmonic drive was directly

connected to a torque-meter to monitor the input torque provided

to the gearbox. The output side of the torque-meter was

connected to one of the test gear shafts via a flexible elastomer

coupling. The test gearbox consisted of a unity-ratio spur

gear pair held by relatively rigid

shafts. Concentric bearing housings

holding the bearings were

mounted on two massive split

pedestals. The shaft of the driven

(output) gear was connected

to a magnetic particle brake with a maximum torque capacity of

400 Nm by means of another flexible coupling. The shafting permitted

optical rotary encoders to be mounted on their free ends

outside the bearing pedestal for measurement of TE. The rotary

encoders (Heidenhain, RON 287) have the capability to measure

18,000 positions per complete rotation.

Figure 2 Quasi-static transmission error (TE) measurement set-up.

- Click image to enlarge

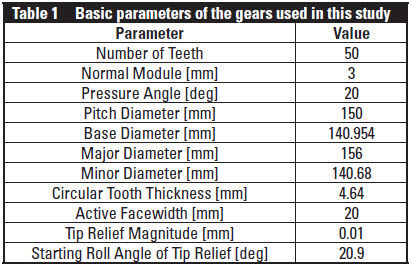

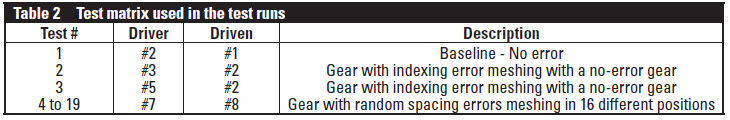

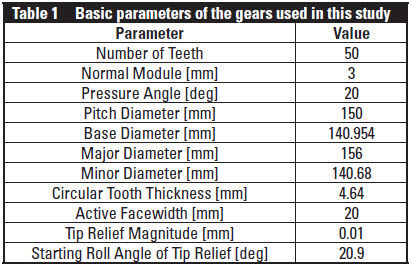

Test specimens and test matrix. Unity-ratio spur gear pairs

were used in this study with an operating center distance of

150 mm. A total of 7 gears with tightly controlled indexing

errors formed the inventory for the test matrix. Two gears with

no indexing errors, three test gears with discrete spacing errors

at a few teeth along with two additional gears with randomized

spacing errors were procured specifically for this study. Basic

gear parameters for these gears are listed in Table 1. Each gear

pair had a theoretical contact ratio of 1.8. The test gears had the

following intentional spacing errors:

- Gears #1, #2: Gears with no indexing errors (in reality, errors

exist but less than 2 μm).

- Gear #3: Gear with a single tooth having a negative 15 μm

spacing error.

- Gear #4: Gear with two consecutive teeth having negative

15 μm spacing errors.

- Gear #5: Gear with two teeth having negative 15 μm indexing

errors with the tooth in between them in the correct position.

- Gears #6, #7: Gears with all teeth having spacing errors with

randomly distributed magnitudes between the range [-15,

15] μm.

Each error was placed in the negative direction, which refers

to the tooth entering mesh later than expected. The negative

direction of the errors was chosen because they were obtained

by removing additional material from the teeth with no error.

Likewise, if a tooth enters mesh earlier than nominal compared

to the previous tooth, the spacing error is positive. Moreover,

a more realistic case where two gears having various different

indexing errors was studied utilizing the gears designated as

Gears #6 and #7. These gears were machined to have random

spacing errors within the range [-15, 15] μm. Furthermore, with

right and left flanks having different error values, these two gears

represented four different random spacing error conditions.

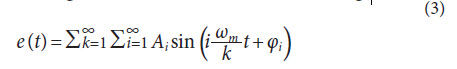

Transmission error measurements. The transmission error

measurement system used two separate encoders to determine

the angular position of each gear shaft. The signals from the

encoders were passed into encoder conditioners. A commercially

available transmission error measurement system was

used to process the conditioned encoder signals to compute the

transmission error. The software has high and low pass filtered

TE time histories of the same data to quantify shaft and mesh

frequency content of the TE signal. This system considers either

the driving pinion (input) encoder or the driven gear (output)

encoder as the reference signal to determine output and input

TE signals (both in μrad), or as a linear displacement along the

line of action as:

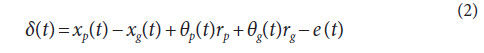

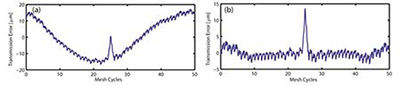

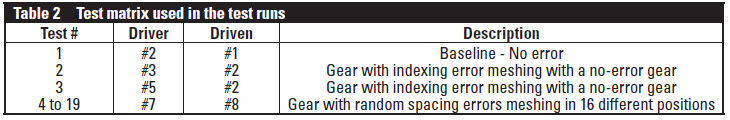

These TE measurements are processed using data segments

corresponding to 16 complete gear rotations. In Figure 3 a

representative measured loaded e(t) is presented from Test #2

at 200 Nm. In Figure 3 (a, b), the unfiltered (raw) and the

high-pass filtered versions of the measured e(t) is presented.

Although the measurements were recorded for 16 complete gear

rotations, only one complete rotation, including 50 gear mesh

cycles, is presented in these figures. These representative measurements

clearly exhibit the intentional indexing error amount

generated on the test gears. With the gear rotational speed of

10 rpm, gear mesh frequency is 8.33 Hz. Accordingly, the measured

TE signal is put through a high-pass filter with a cut-off

frequency slightly higher than 0.167 Hz, removing frequencies

equivalent to one shaft order frequency and below. A family

of baseline tests of the two no-error gears was run first at all

of the operating conditions specified. The sinusoidal waviness

in Figure 3(a) is the once-per-revolution amplitude caused by

the pitch line run-out error of the gear pair. Once such low-frequency

content is removed by the high-pass filter, the remaining

TE is seen to be dominated by the gear mesh orders (50, 100,

150, etc.), and the resultant TE time histories reveal mesh frequency

components of TE. It is also observed from the filtered

data that certain tooth-to-tooth variations exist. This is a direct

result of a small amount of spacing errors present in these noerror

gears — despite all efforts to minimize them. As a result,

the frequency spectrum has other non-zero, non-mesh harmonics

— especially below the fundamental gear mesh order of 50.

Figure 3 Measured static TE from Test #2: (a) unfiltered TE; (b) filtered TE.

- Click image to enlarge

Results and Discussion

In this section, impact of indexing errors on dynamic response

of gear pairs is presented utilizing predicted dynamic transmission

error time histories and corresponding frequency spectra.

Dynamic transmission error (DTE) predictions are compared to

the baseline measured quasi-static transmission error e(t) time

histories (STE) and frequency spectra of the corresponding gear

pairs. Here results are reported in terms of dynamic transmission

error, as it provides the most direct physical link between

the measured STE and predicted DTE while the model is also

capable of predicting dynamic mesh force, dynamic bearing

forces and displacements and gear motions, as defined in all 6

degrees of freedom.

First, a linear time-invariant (LTI) version of the same

dynamic model was run to determine the resonant frequencies

and corresponding mode shapes of the baseline gear pair with

no indexing errors. The resonant frequencies were found to be

at 3,370, 5,940 and 7,300 rpm. As pointed out earlier, dynamics

regarding the y-direction motions were excluded from the

discussion, as they can be treated independently. Later, dynamic

response and mesh force spectra of the same baseline gear

pair were predicted utilizing both LTI and NTV versions of the

model to identify the off-resonant speed (frequency) ranges of

the system within which specific frequencies were chosen for

further analysis. The off-resonant frequencies that were used for

further analysis are 400 rpm, 1,300 rpm and 2,100 rpm. At these

off-resonance speeds, magnification on the TE due to the gear

pair dynamics can be clearly observed without the extra amplifications

due to mesh resonances and nonlinear effects.

Although numerous test cases, along with the corresponding

dynamic model predictions, were carried out, a subset of the

results is reported here to illustrate the importance of incorporating

indexing errors into the gear design and dynamics considerations.

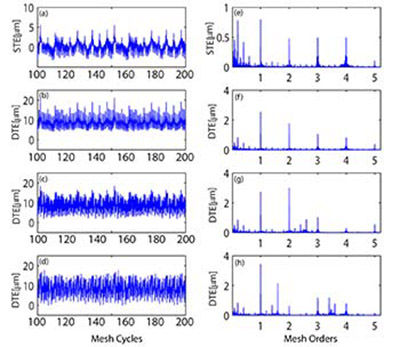

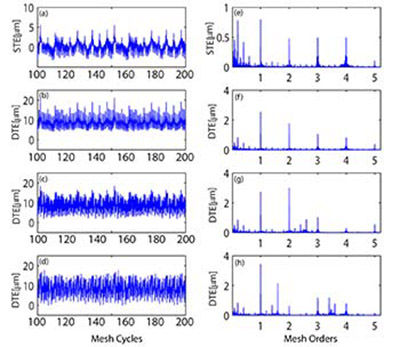

Results from Test #1 that included the baseline gears

with no indexing errors along with the corresponding dynamic

transmission error predictions are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Measured static TE (a) along with predicted dynamic TE time histories from Test#1 at 400,

1,300 and 2,100 rpm (b-d); and corresponding frequency spectra (e-h).

- Click image to enlarge

In Figure 4(a) a measured STE time history is given between

gear mesh cycles 100 to 200. This mesh cycle range was

intentionally chosen to exclude any transient effects taking

place — especially for the initial cycles for the predicted DTE.

In addition, measured STE and predicted DTE traces were presented within the same mesh cycle

ranges to clearly demonstrate the

dynamic magnification effects. It is

apparent from both Figure 4(a), and

its corresponding frequency spectrum

Figure 4(e), that even baseline

gears had limited indexing errors

on them along with teeth deflection

and other geometric imperfections

that contributed to the

STE. Predicted DTE at 400 rpm,

1,300 rpm and 2,100 rpm is presented

in Figure 4(b-d), along with their

corresponding frequency spectra

in Figure 4(f-h). Although it is

clearly observed from the comparison

between time histories for STE

and DTE at different speeds how

dynamics play a significant role on

TE, note also that frequency spectra

are intentionally presented in

gear mesh orders to help us detect

the changes at main mesh order and

its harmonics, shaft orders and also

gear pair resonances at once. For

instance, in Figure 4(g), when gears

were rotating at 1,300 rpm, resonant

peak revealed at the mesh order 2.8

that corresponded to the second

mode (torsional mode) of the system.

Similarly, in Figure 4(h), when

gears were rotating at 2,100 rpm,

resonant peaks at the mesh orders

1.6 (torsional mode) and 3.6 (coupled

torsional-translational mode)

were revealed due to gear pair

dynamics.

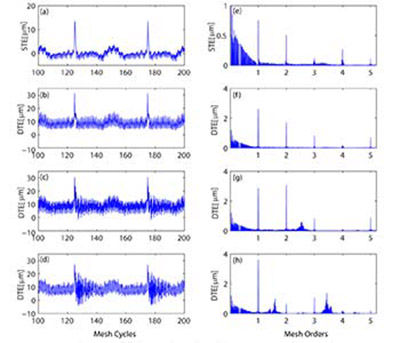

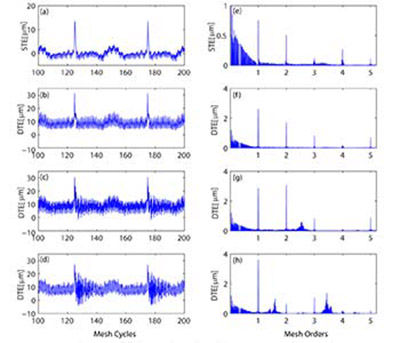

In Figure 5 STE and DTE time

histories, and corresponding frequency

spectra from Test #2, are

given following the same sequence

in Figure 4. Test #2 included a gear

with no indexing errors and a pinion

with an intentional spacing error

of 15 μm at tooth #25 (Fig. 3). The

peaks that are seen in the filtered

STE time trace (Fig. 5(a)) exhibit

how the discrete spacing error

of the particular tooth on the gear

comes in mesh and causes a sudden

increase in the measured STE once

during a complete rotation of the

gear; i.e. — once in every 50 mesh

cycles. The fact that one of the teeth

has discrete spacing error, whereas

all the other teeth have almost perfect

spacing, breaks the cyclo-symmetricity

of the meshing action and thus mistunes the dynamics of the gear

pair. This can essentially be observed in

Figure 5(a-d), when the same gear pair

was used but was run at sequentially

increasing speeds. Especially, in Figure

5(c) and (d), when the gears were rotating

at 1,300 and 2,100 rpm, respectively,

time traces exhibit how more than once

mesh cycle was affected due to a single

discrete spacing error on the gear.

Figure 5 Measured static TE (a) along with predicted dynamic TE time histories from Test #2 at

400, 1,300 and 2,100 rpm (b-d); and corresponding frequency spectra (e-h).

- Click image to enlarge

Under dynamic conditions, teeth

do not only deflect due to the applied

external load, but also oscillate about

this pre-deflected position under the

influence of dynamic loads. Moreover,

indexing errors cause time and phase

lags (or leads) on the mesh timing that

can cause dynamic loads to become

magnified and also modify them to

where they become more impulsive.

Gear contact ratio reinvigorates the gear

pair dynamics as it is the most important

design parameter that decides upon

when and how much load will a particular

tooth carry. Moreover, mesh damping

strongly influences the dynamic

response of the gears, but is hard

to determine and also to change. The

other important point to stress here is

the energized broad-band shaft order

regime and its physical reasoning. In

Figure 5(e-h), although run-out effects

were excluded from the measured STE,

shaft order (orders lower than the fundamental

mesh order) peaks and integer

multiples are revealed. The main

reason is that the teeth with deterministic

spacing error repeats and leaves its

signature once in every rotation of the

gear, leaving a strong mark on the frequency

spectrum. This effect becomes

even more significant when dynamics

come into play at higher speeds. The

peaks revealed at integer multiples of

the shaft orders are due to the amplitude

and phase modulation of the TE

and will be further studied in a subsequent

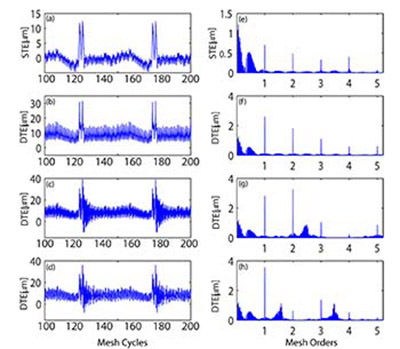

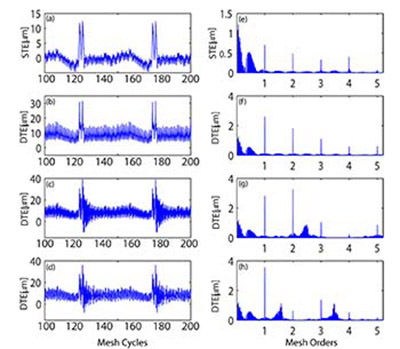

study by the authors. In Figure

6, results from Test #3, where an intentional

deterministic indexing error pattern

of 0-15-0-15-0 μm was used on the

pinion, is presented. In this case there is

a single, intentionally misplaced tooth

on the gear that was followed by both

a perfectly positioned and misplaced

tooth. This error pattern introduced

another layer of complications to the

resulting frequency spectra by strengthening 2× shaft orders along with 1× shaft orders. The complicated

phasing relationship affected the resulting peak distribution

in the frequency spectra, which is more clearly visible from

orders lower than the fundamental (1×) gear mesh order.

Figure 6 Measured static TE (a) along with predicted dynamic TE time histories from Test #3 at

400, 1,300 and 2,100 rpm (b-d); and corresponding frequency spectra (e-h).

- Click image to enlarge

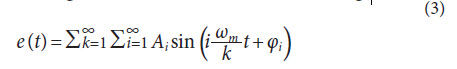

The measured STE and predicted DTE thus far have included

intentionally created, deterministic indexing errors on the gear.

In Figure 7, however, results from Test #4, which included random

spacing errors on the pinion, are presented. The random

error pattern is definitely more representative of the real indexing

error patterns observed on the gears manufactured using

cutting, shaping etc. operations. Although randomly distributed,

spacing errors were kept between the range [-15, 15] μm.

As seen both from the time traces and the corresponding spectra

(Fig. 7), random spacing error patterns cause a truly broadband

excitation, thereby activating the resonant peaks and shaft

orders — regardless of gear speeds.

Conclusions

Figure 7 Measured static TE (a) along with predicted dynamic TE time histories from Test #4 at 400,

1,300 and 2,100 rpm (b-d); and corresponding frequency spectra (e-h)

- Click image to enlarge

In this study a model to predict gear pair dynamics using measured,

long-period quasi-static transmission error of a gear pair

was developed. This model uses measured, broadband static TE

excitation with any time and frequency resolution and predicts

dynamic gear mesh force, dynamic TE and bearing forces. Both

time domain and frequency domain results can be obtained at

steady-state and transient speed conditions. First, gears were

intentionally mistuned through tightly-controlled deterministic

and stochastic indexing errors, and resulting gear pair dynamics

were compared against a baseline gear pair with no indexing

errors (minimized, but not zero). Cases with gears having

limited, discrete indexing errors increase the dynamic response

during a limited number of mesh cycles, thus increasing the

dynamic response. Their frequency spectra are enriched by

additional shaft order peaks due to amplitude and frequency

modulations caused by the perturbed transmission error excitation.

Cases with random indexing error exhibit even greater

broadband response, having peaks at shaft order and its integer

multiples along with mesh order and its harmonics. They

exhibit significantly more energy content at frequencies lower

than the fundamental mesh frequency. The broader spectrum

is caused by the broadband TE excitation causing a frequency

modulated dynamic mesh force spectrum.

References

- AGMA Technical Standards. ANSI/AGMA 2015-1-A01.

- Remmers, E.P. “Gear Mesh Excitation Spectra for Arbitrary Tooth Spacing

Errors, Load and Design Contact Ratio,” J. of Mech. Des.100, 1978, 715–722.

- Mark, W.D. “Analysis of the Vibratory Excitation of Gear Systems, Part I:

Basic Theory,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 63 (5), 1978, 1409–1430.

- Mark, W.D. “Analysis of the Vibratory Excitation of Gear Systems, Part II:

Tooth Error Representations, Approximations, and Application,” J. Acoust.

Soc. Am. 66 (6), 1979, 1758–1787.

- Kohler, H. and R. Regan. “The Derivation of Gear Transmission Error from

Pitch Error Records,” J. Mech. Eng. Science, 199 (C3), 1985, 195–201.

- Mark, W.D. “The Role of the Discrete Fourier Transform in the Contribution

to Gear Transmission Error Spectra from Tooth Spacing Errors,” J. Mech.

Eng. Science, 201(C3), 1987, 227–229.

- Kohler, H., R. Regan and W. D. Mark. “The Derivation of Gear Transmission

Error from Pitch Error Records,” Discussion, J. Mech. Eng. Science, 201(C3),

1987, 230–232.

- Padmasolala, G., H. H. Lin and F. B. Oswald. “Influence of Tooth Spacing

Error on Gears With and Without Profile Modifications,” NASA/TM 2000-

210061 PTG-14436, October 2000.

- Wijaya, H. “Effect of Spacing Errors and Runout on Transverse Load Sharing

and Dynamic Factors and Idler Gear Dynamic Analysis,” MS Thesis, The

Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, 2001.

- Spitas, C. and V. Spitas. “Calculation of Overloads Induced by Indexing

Errors in Spur Gearboxes Using Multi-Degree-of-Freedom Dynamical

Simulation,” J. Multi-Body Dynamics 220, 2006, 273–282.

- Milliren, M. “An Experimental Investigation Into the Various Errors on the

Transmission Error and Root Stresses of Spur Gears,” MS Thesis, The Ohio

State University, Ohio, 2011.

- Handschuh, M. An Investigation into the Impact of Random Spacing Errors

on Static Transmission Error and Root Stresses of Spur Gear Pairs,” MS

Thesis, The Ohio State University, Ohio, 2013.

- Tamminnana, V.K., A. Kahraman and S. Vijayakar. “On the Relationship

between the Dynamic Factors and Dynamic Transmission Error of Spur

Gear Pairs,” J. Mech. Des., 129, 2007, 75–84.

- Kahraman, A., J. Lim and H. Ding. “A Dynamic Model of a Spur Gear Pair

with Friction,” 12th IFToMM World Congress, Besançon (France), June

18–21, 2007.

- Blankenship, G. W. and A. Kahraman. “Steady State Forced Response of a

Mechanical Oscillator with Combined Parametric Excitation and Clearance

Type Nonlinearity,” J.Sound and Vibr., 185, 1995, 743–765.

- Windows LDP. The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, 2013.

- External2D. Advanced Numerical Solutions, Inc., Hilliard, Ohio, 2013.

About Author

Dr. Murat Inalpolat is an

Assistant Professor in the

Department of Mechanical

Engineering at The University

of Massachusetts Lowell. He

has more than a decade of

experience in the areas of

structural health monitoring;

damage detection/diagnostics and prognostics;

structural dynamics and acoustics; and signal

processing — along with rotating machinery

dynamics and noise. His most current research

focuses on structural health monitoring,

diagnostics, prognostics, and operational

damage detection and identification. He also

has extensive project experience working on

aircraft- and rotorcraft-related projects obtained

while working at the General Electric Global

Research Center. He has been a reviewer

for such publications as the Journal of Sound

and Vibration; Mechanical Systems and Signal

Processing; and ASME Journal of Mechanical

Design. Inalpolat was previously awarded by CTI

(Car Training Institute of Germany) the prestigious

“Young Drive Experts” award based on his quality

of the research

Michael J. Handschuh

is a PhD student in the

Mechanical and Aerospace

Department of The Ohio State

University, having received

his BS and MS degrees in

Mechanical Engineering in

2011 and 2013, respectively.

Handschuh is a Graduate Research Associate

with the Gear and Power Transmission Research

Laboratory.

Ahmet Kahraman is

Howard D. Winbigler

Professor of Mechanical

and Aerospace Engineering

at the Ohio State University.

He is the Director of Gleason

Gear and Power Transmission

Research Laboratory. He also

directs the Pratt & Whitney Center of Excellence

in Gearbox Technology.