Very High Cycle Fatigue Testing of AMS 6308 Steel

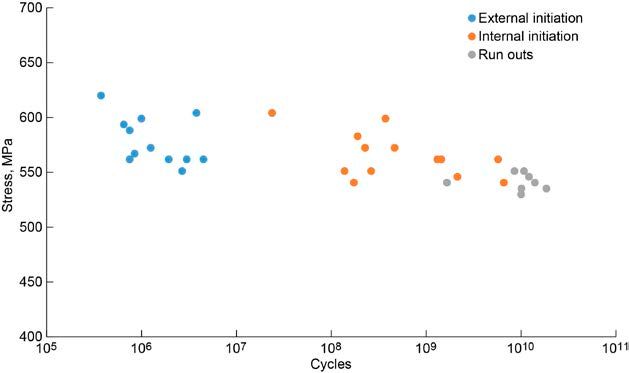

Lightweight and reliable gearboxes are required for helicopters and future electrical vertical take-off and landing aircraft. Mechanical gears in these applications experience more than 107 fatigue cycles over their operating life and between maintenance intervals. High-strength materials have been shown to fail due to fatigue past 107 stress cycles (Ref. 1). In this fatigue regime, the initiation point for the fatigue crack shifts from the surface to internal defects in the material, and the fatigue stress versus cycles curve has a different slope than the low-cycle fatigue regime (Refs. 1 to 4).

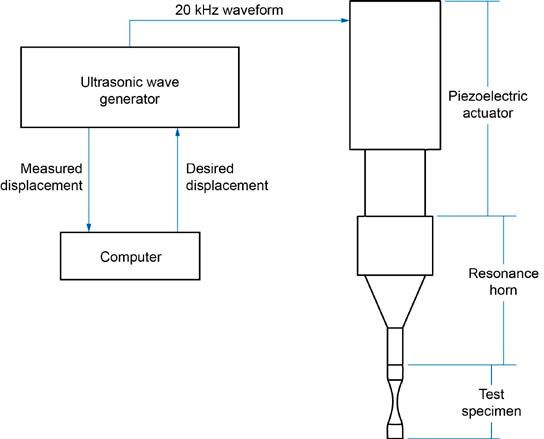

Traditional methods of predicting gear fatigue strength past 107 cycles rely on empirical extrapolation of the 107traditional fatigue strength of the material (Refs. 5 and 6). Extrapolation is used because data for gear steel strength past 107 cycles is rare due to the time and cost of testing to these high cycle counts using traditional fatigue testing methods. Ultrasonic fatigue testing is a material testing method that allows fatigue stress cycles to be generated in a specimen at 20 kHz. Correspondingly this method is practical for creating material fatigue data in the very high cycle fatigue regime (107 to 1010 cycles) (Ref. 1). Ultrasonic fatigue can lead to slightly different material fatigue strength predictions relative to predictions obtained with traditional fatigue test methods due to environmental effects, temperature rise, and the low stressed volume in the specimens (Ref. 7).

In this paper, ultrasonic fatigue testing results for “core hardened” AMS 6308 gear steel are presented. AMS 6308 is a gear and bearing steel with high tempering resistance and high hot hardness case targeted to high temperature applications (Ref. 8). The material tested in this paper is “core hardened” such that it is representative of gear tooth core material. Core hardening of the material is accomplished by masking the specimens and processing through the normal AMS 6308 case hardening heat treatment process. Core material strength is not directly applicable to the bending fatigue strength of gear teeth; however, understanding core material strength establishes a baseline for strength improvements achieved through case carburizing and could provide valuable information for the development of heat treatments for very high cycle fatigue strength. Since crack initiation shifts form the surface to internal location in the specimen in the very high cycle fatigue regime, achieving the right combination of case depth and residual stress could extend gear steel lifetimes. The results in this paper will be used to inform future ultrasonic AMS 6308 bending fatigue testing using the method described in Ref. 9 that is able to capture the effects of gear tooth heat treatment in a relevant bending fatigue stress environment.

Specimen Design

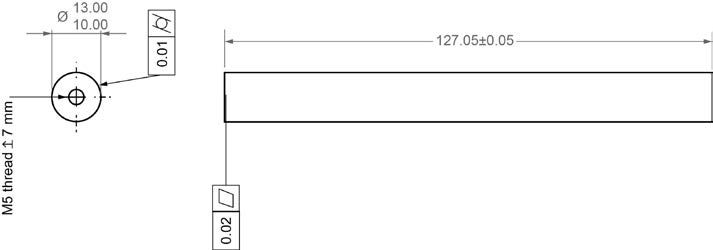

Past work by the author (Ref. 10), showed that using an axial ultrasonic fatigue specimen design as described in Reference 1 led to significant uncertainty of the stress state of the specimen since the ultrasonic horn used to excite the test specimen has an observable displacement noise level of ~0.05 μm. For the specimens in this paper, a new specimen design was carried out with the goal of reducing the uncertainty of the stress state to less than 1 percent. The dynamic modules of test specimens were measured using the method described in Ref. 1. A mean value for the measured material dynamic module based on seven specimens was 201.8 GPa. This measured value was used in all specimen modeling. Appendix A provides the specimen drawing (Figure 4) and specimen test results (Table I) for the dynamic modules of core hardened AMS 6308.

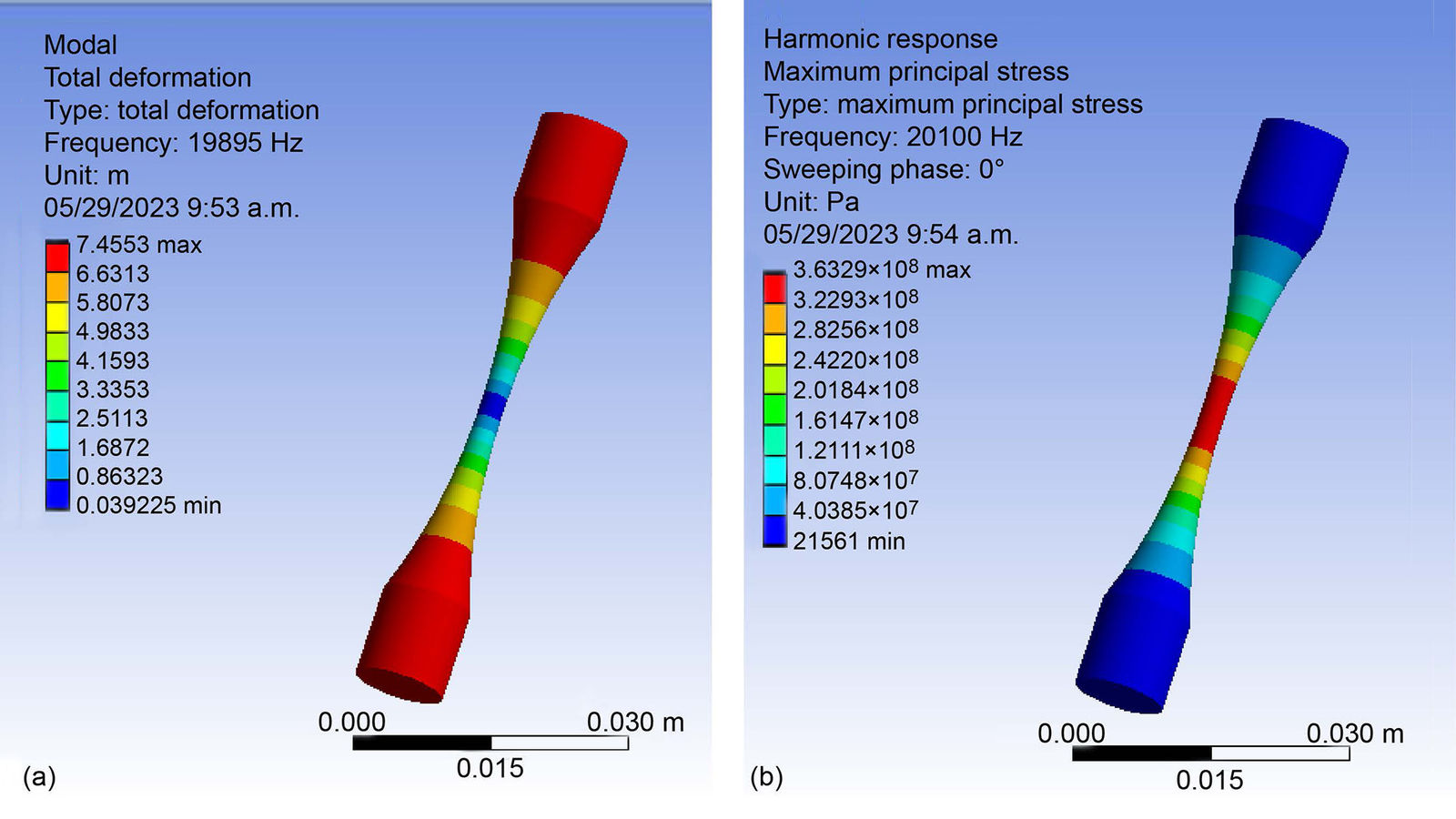

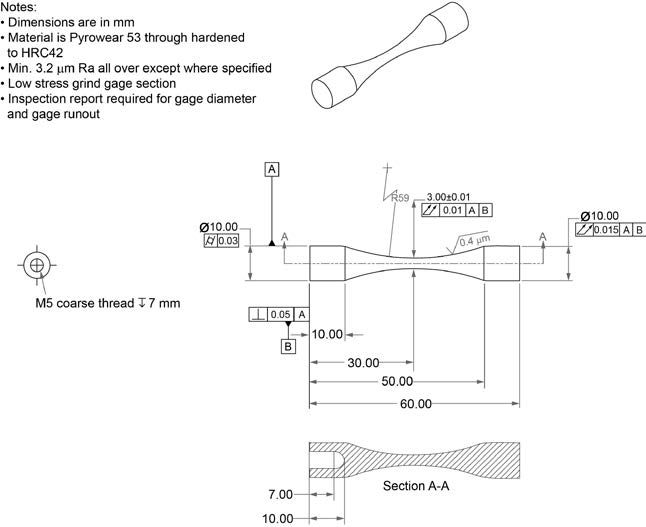

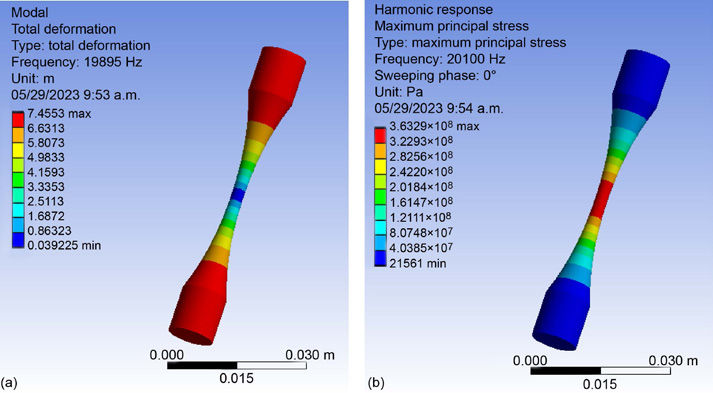

Appendix B provides the drawing for the developed AMS 6308 specimen (Figure 5). Minimum size end sections that are 10 mm long are used to reduce the slope of the stress versus displacement response of the specimen such that a 0.05 μm displacement uncertainty results in a stress uncertainty of ~1 MPa. Finite element analysis was used to achieve the specimen design. Figure 1 shows the FEA model results for specimen mode shape deformation and stress response.

The specimen manufacturing was carried out in a four-step process:

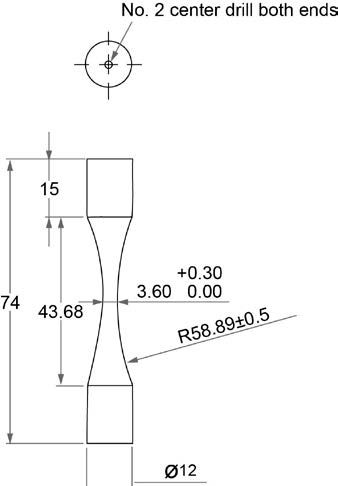

- Premachining per drawing (Figure 6) in Appendix C.

- Heat treatment per process defined in Appendix D.

- Low-stress grind the gage section to desired dimensions.

- Final machine the part to length. Appendix B provides final part geometry (Figure 5).