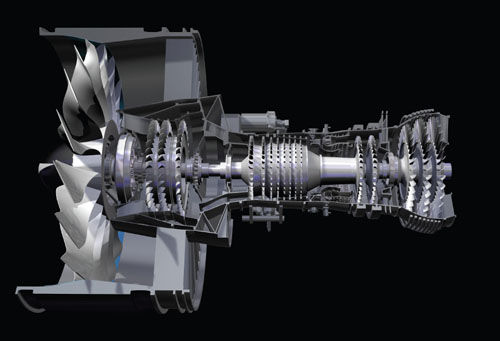

The thrust of things to come. Gear professionals, engine designers and others in the industry know, of course, that turbofan jet engines are not new, and they are in fact standard for today’s jets. P&W’s Saia provides for the rest of us a short course in conventional jet propulsion.

“Jet engines produce thrust by pushing air through a large fan at the front of the engine. A small portion of that air is compressed, mixed with fuel and ignited to power a turbine at the back of the engine, which in turn spins a shaft that runs through the engine to drive the engine’s fan. To improve fuel efficiency, engine makers work to maximize the amount of air pushed through the fan (bypass air), while using as little fuel as possible to drive the fan. The ratio of air pushed through the fan to the air mixed with fuel to drive the fan is called bypass ratio; the higher the bypass ratio, the more fuel-efficient the engine.”

But, P&W’s Saia explains, conventional turbofan engines have limits, in that “As the fan diameter increases to increase bypass ratio, the turbine must also grow to create more power to drive the larger fan. Fans want to turn at slow speeds, while turbines want to turn at high speed. With the fan and turbine directly connected by the shaft, a compromise must be made to maximize fan diameter (low speed) at the best turbine speed (a slower-than-optimum speed).

“Slower-turning turbines require more stages and higher airfoil counts to power the fan; the additional stages and airfoils increase the engine’s weight and operating costs. There becomes a point where the added weight and inefficiency of the larger turbine has cancelled out any fuel efficiency gained by a larger fan.”

Which presents the challenge—how to reduce the speed of the outer ring gear in a significant way?

Answer: the addition of a reduction gear box—or transmission system—comprised of a star gear system with five stationary gears. As Saia explains, the gear box decouples the fan from the turbine so that each component can turn at its optimum speed, while also allowing for a lighter, more efficient turbine to turn at a higher speed in driving a much larger, slower-turning fan. The marrying of a faster-turning turbine with a slower-turning fan results in new-found fuel efficiency at a much-reduced noise level. In fact, the addition of the gearbox provides a low-pressure turbine speed of three times that of the fan. The system also includes a “swept,” aerodynamically enhanced fan for additional efficiencies.

Burning “greener” gas. So how does all of this reduce fuel consumption, cabin noise and pollutants? To break it down further, Saia says, consider that with a typical, direct-drive turbofan engine the limitation is that its turbine is most efficient, i.e.—creating the most power for the least fuel consumption—when it is rotating at optimum speed. And, as mentioned, this type of engine’s turbine and fan are unalterably linked, presenting an unavoidable compromise in speed.

But, says Saia, “The GTF engine breaks this paradigm. This game-changing engine architecture introduces a reduction gear system allowing both the fan and turbine to operate at their optimum speed. By turning a large fan—increasing the bypass ratio of the engine—fuel efficiency is improved by more than 12 percent. This is directly related to a 12 percent improvement in CO2 emissions. The slower-moving fan produces much less noise—50 percent less than today’s engines. We’ve also introduced an advanced combustor to reduce NOx emissions by 55 percent.

“The GTF engine also delivers an engine design which is shorter and lower-weight than today’s power plants.”

A close-up of the five stationary gears in the geared turbofan engine speed reducer gearbox.

With the critical, grind-it-out R&D completed, Pratt & Whitney has big plans for the GTF engine. And why not?

“(Last year), Pratt & Whitney’s Geared Turbofan engine was selected as the exclusive power for the new (aforementioned Mitsubishi Regional Jet; officially launched this March with an order from All Nippon Airways) and the proposed Bombardier CSeries mainline aircraft,” says Saia. “The CSeries is expected to launch later this year. Both aircraft are scheduled to enter service in 2013.”

What next—alternative jet fuel?