With the way that they are designed, almost all vacuum furnaces work even better in higher temperatures. Unlike older gas atmosphere furnaces that employ “high temperature” exotic nickel or cobalt alloys for radiant tubes and fans, and for load support and transport, vacuum furnace designs mostly do not. Thus, higher process temperatures will not degrade the furnace life and will not increase maintenance costs nor add more downtime. Therefore, to process more affordably with LPC, it is desirable to increase the process temperature to speed things up. Much has been written about higher carburizing temperatures and how it is possible to cut cycle times in half (Ref. 4), so it will not be dwelled on here. Suffice it to say, higher temps really speed things up, shorten cycles and increase productivity.

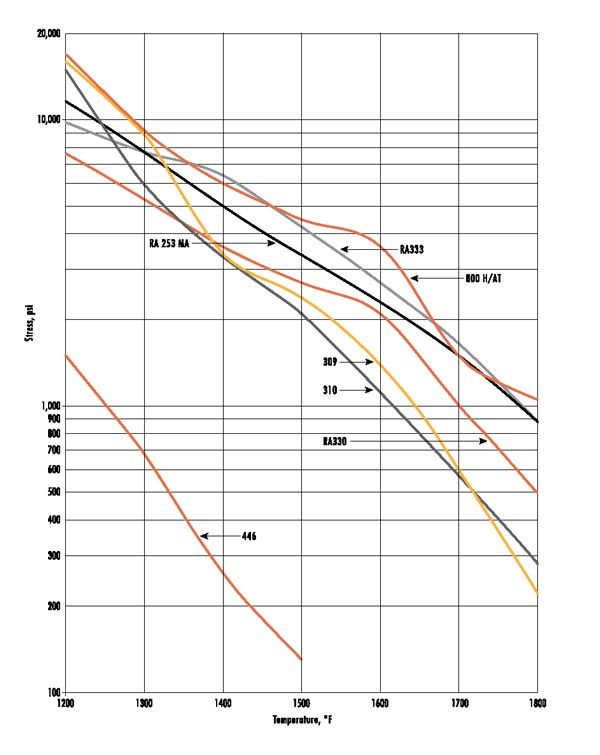

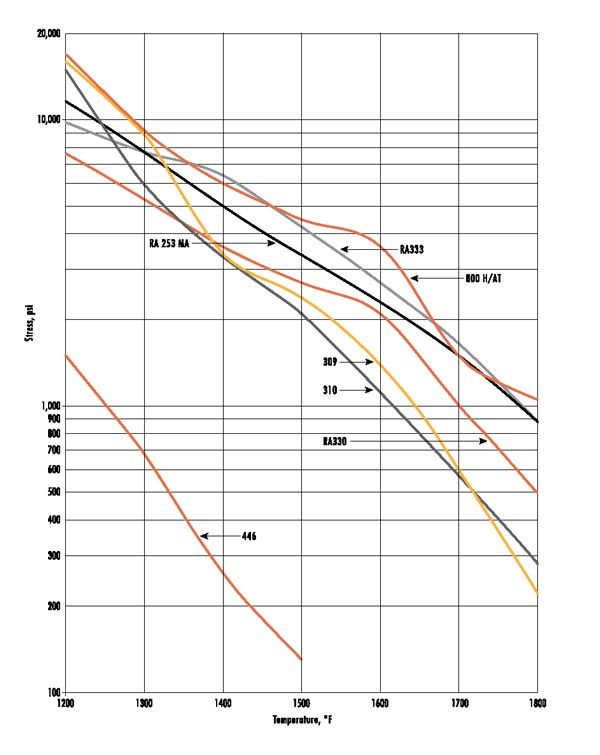

In atmosphere furnaces, even with exotic, expensive metal alloys used in the hearth components and radiant heating tubes, the alloys will degrade with a relatively modest increase of 150°F, say from 1,700°F to 1,850°F. The figure on page 23 shows RA330 (a common heat treating alloy) and other alloy profiles at 1,700°F and 1,800°F. Creep rates increase and strength decreases substantially (as can be seen, at 1,800°F, most of the alloys are at very low strengths [the scale is logarithmic]).

And with many alloys, if you add in the harsh atmosphere of gas carburizing, problems get even worse. Any furnace designer must balance the need for long furnace life with competitive furnace pricing and maintenance cost challenges.

Therefore, by understanding the science of LPC, it is important to know that these systems are designed to run shorter cycles at higher temperatures, and by going from, for instance, 16 hours to 8 hours, one can double productivity (throughput) in a single chamber. Time is money. Less time means less costs to the customer and more profits for the CHT shop.

Atmosphere Carburizing Rather than LPC

The analysis of gas carburizing compared to LPC can get complicated and it is rather subjective. Some of the hard rules for using conventional gas atmosphere processing, when possible are:

- Carbonitriding

- Small lots

- Mixed loads of parts

- Low processing temperatures desired

For carbonitriding, ammonia is added to make the surface very hard, yet the needs are often for shallow cases. These are shorter cycles. Ammonia under vacuum is very unstable. This means it breaks down (dissociates) very fast. With LPC, in order to do a 30-minute carbonitriding segment, it may require just as much time to reduce the temperature. Also, the carburizing and ammonia segments are usually separated. Thus, carbonitriding is best left to the quick, easy, and inexpensive gas atmosphere method.

Small lots from a customer necessitate just as much initial set-up time as a constantly running program which can last for three or more years. It is much easier to drop these small lot loads into the daily grind of the gas atmosphere carburizing department than to set up and confirm a LPC cycle.

Moreover, many commercial shops may enjoy mixing parts to maximize load size, but with LPC, this gets more complicated, as mixed loads need the surface area to be calculated.

Finally, gas atmosphere carburizing works fine at lower temperatures and the equipment will last longer. LPC, especially for deeper case depths, really makes more sense at higher processing temperatures to speed the process along. Sometimes, the CHT shop will get a spec that limits processing temperature to 1,700°F or 1,750°F. It is then probably easier to use gas atmosphere carburizing. As mentioned, gas atmosphere furnace systems prefer lower temperatures since it is not as hard on the equipment. With LPC, one really wants to run at or above 1,800°F (990°C).

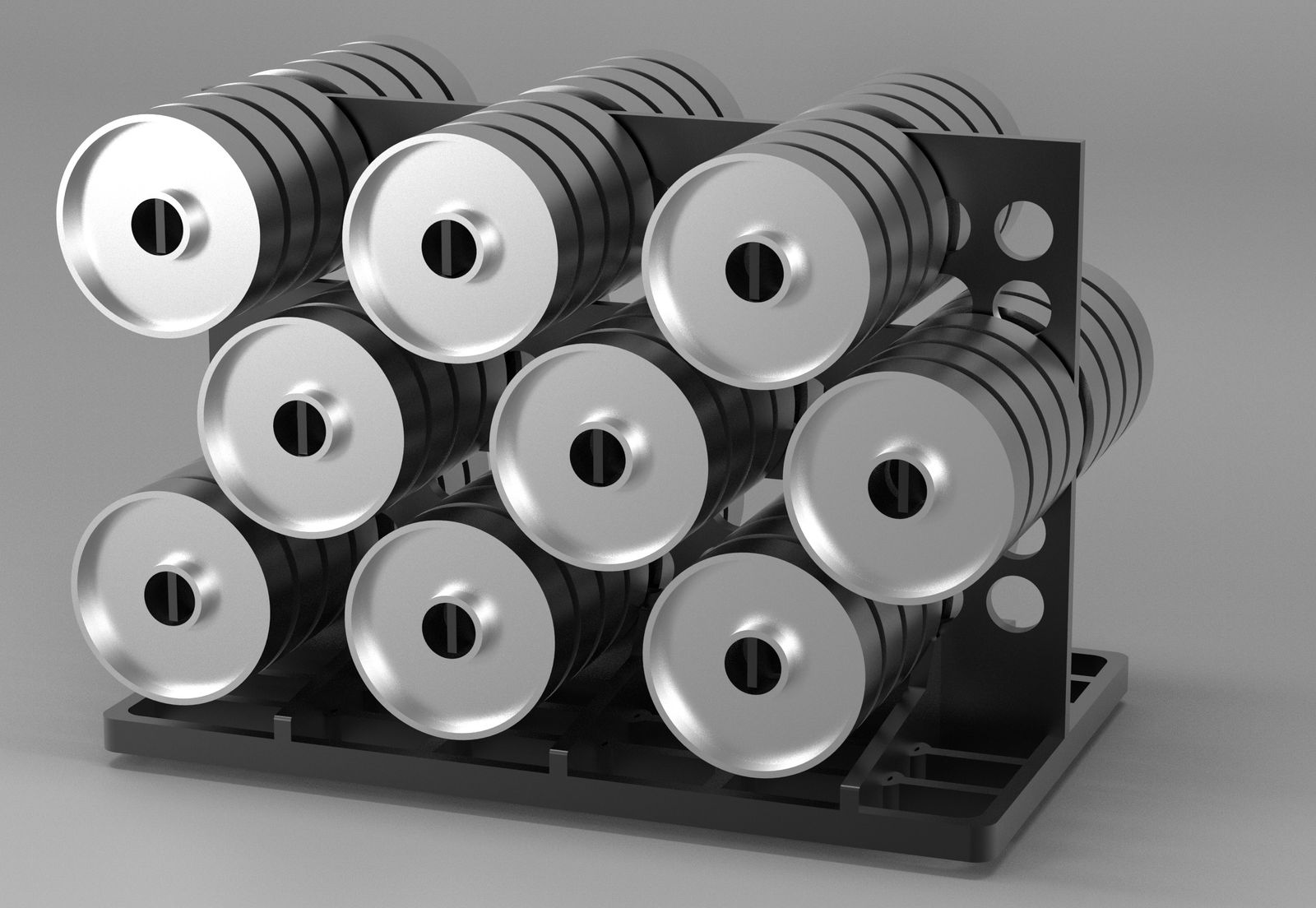

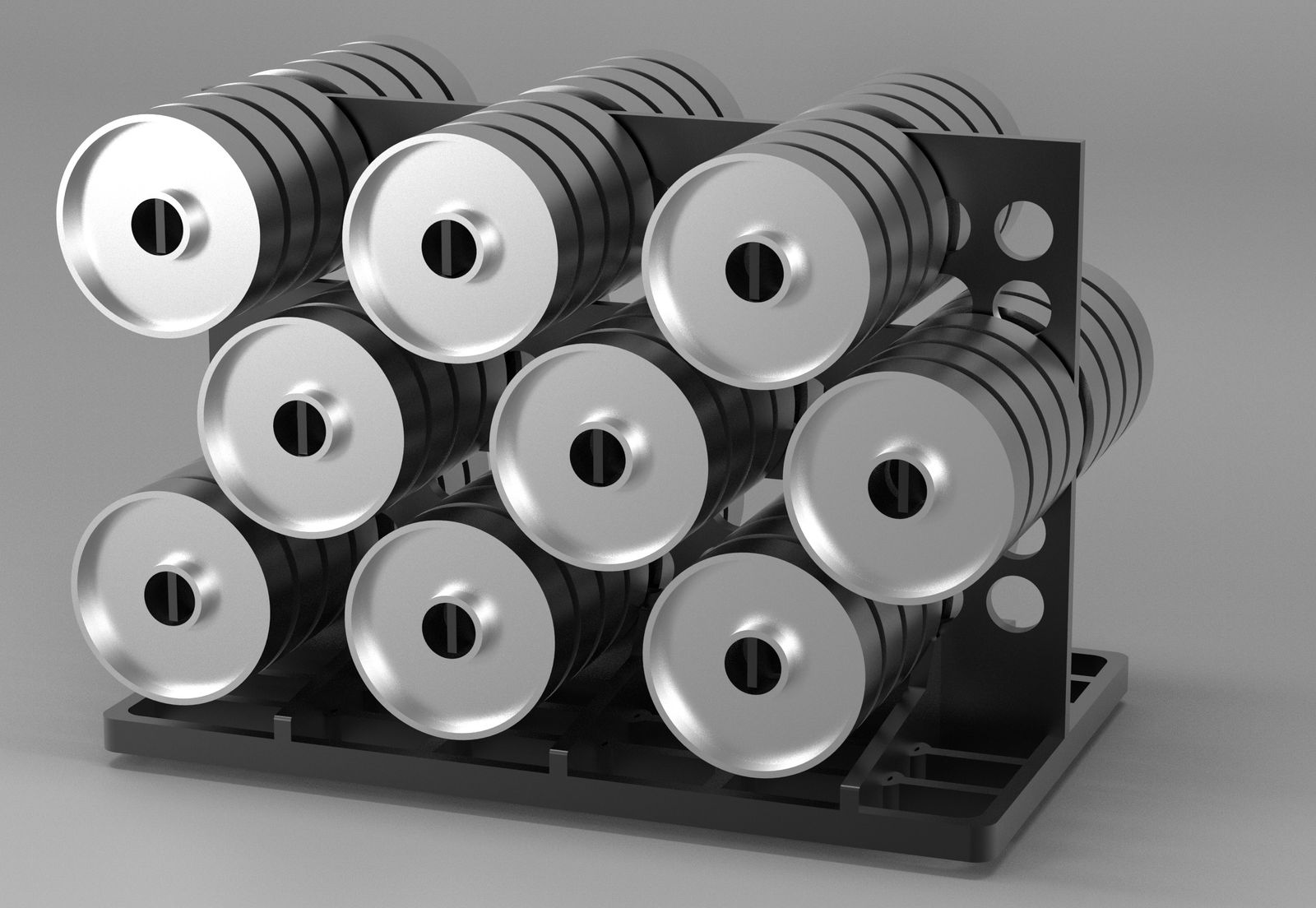

Modern high production low pressure carburizing furnaces at Nitrex HTS – Aurora, IL.

Modern high production low pressure carburizing furnaces at Nitrex HTS – Aurora, IL.

When to Use LPC

OK, so why is LPC both “better” and “affordable”?

- Mixing of gases is different in a vacuum than under atmospheric pressure. It is easier to deal with blind holes and difficult contours with LPC.

- Vacuum furnaces are designed to run at higher process temperatures as they do not use conventional alloys of construction.

- Vacuum is, by definition, cleaner.

- Oil quenching allows for more densely designed loads.

Mixing gases in vacuum? Yes, this is very important. Vacuum carburizing is performed in a pressure range of around 10 mbar (1,000 mbar is atmospheric pressure). When a gas is introduced into such a “vacuum”, the gas will behave in an ideal manner and expand to fill the space where there are no gas particles. In effect, this is mixing without the need for fans. This is because, during evacuation, there are less collisions of other gas particles as we evacuate more and more particles. This means blind holes will fill with gases by definition. The process is more complex, but this is a guiding principle. There is an excellent article on this concept (Ref. 7).

Most vacuum furnaces today are designed with water-cooled walls, and they use carbon and graphite insulating and heating element materials. These furnaces are easily designed for constant use at over 2,000°F. Most atmosphere furnaces struggle to not deteriorate at 1,750°F, as they use “high temperature” alloys, and the carbon gases and high temperatures attack and degrade these alloys. Few commercial shops will gas carburize at 1800°F and above, even though it is faster. As mentioned before, there are very few exotic nickel or cobalt alloys that perform well, long term, in a carburizing atmosphere and at temperatures of 1,850°F or above (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Minimum creep rate for various high temperature alloys, 0.0001 percent per hour, strength graph (Source: Rolled Alloys, Inc. Performance Guide).

Figure 1 Minimum creep rate for various high temperature alloys, 0.0001 percent per hour, strength graph (Source: Rolled Alloys, Inc. Performance Guide).

The whole process of vacuum heating and cooling is cleaner and devoid of oxygen. In conventional processes, oxygen (and water vapor) is everywhere, hence oxygen probes are used to measure carbon potential. These trace amounts of oxygen results in IGO/IGA and surface finish issues.

It seems most LPC furnaces historically were sold with high pressure nitrogen gas quenching (HPGQ). The problem here is that most steels that manufacturers want to carburize need oil quenching rates. When one complicates this with heavier parts, and load sizes need to be less dense with HPGQ to get uniform gas flows and quenching rates, it is easy to see why it was more expensive and has remained less popular.

There have been some detailed studies performed, and one such study was reported by Herring (Ref. 8).

Methods for Maximizing Value – Tooling Design

Because the equipment for LPC is expensive and furnace chamber sizes (and hence load sizes) are often not as large due to gas quenching limitations, users need to know some tricks to increase load sizes and, in turn, productivity.

In order to maximize weights and use higher temperatures, rethinking load tooling is a requisite.

In order to maximize weights and use higher temperatures, rethinking load tooling is a requisite.

Fixtures for any furnace can get expensive and this fixture tooling is often bulky, heavy, and made from the same alloys that we have been discussing. As well, high temperature alloys that can survive a carburizing atmosphere and constant oil quenching stresses are not cheap! Constant oil quenching and high temperature carburizing are very destructive to alloys. Throw in the higher process temperatures desired with LPC, and we have problems. But the worst one is that we are using heavy alloys and reducing the ability to add parts to the load that can be processed and make money, due to the load weight limitations of any furnace.

As mentioned before, LPC has three loading limitations — surface area, separating parts properly, and weight. Alloys are heavy and, at high temperatures, tooling fixtures need to be built bulky and heavy. This reduces as much as one third of available load capacity.

CFC fixtures can be as much as 10 percent of the weight of alloy fixtures. So, in a 1,500 lb. maximum load, if alloy fixtures were 500 lb., then we could save over 400 lb. and use that extra load for money making parts instead (Ref. 5).

CFC, unlike alloys, retains its strength at higher temperatures, so it can be built without designing for temperature-related substantial reductions in strength, as with alloys. At these high use temperatures, alloys exponentially lose their strength. As well, CFC fixtures can easily handle process temperatures up to 2,000°F. The only limitation with CFC relates to contact points with metal parts at elevated temperatures (Ref. 5).

CFC is not as “robust” as alloys in the day-to-day rigors of running a heat treat operation. For this reason, combinations of CFC-alloy designs for fixtures also have been used. In Figure 4, we show a more robust cast tray made of a high temperature alloy, with the CFC fixture mounted on top. This uses the strengths of both designs and accepts some heavier weights as a trade-off to increase robustness, limit breakage and ease transferring loads at high temperatures. The article (Ref. 5) discusses CFC fixtures, oil quenching and tempering.

Future Considerations

Carburizing in a vacuum low pressure environment is not new. However, even today, the amount of carburizing performed by atmospheric gas carburizing far outweighs the use of LPC. Using LPC requires a commitment to the process and its benefits. Investing in LPC requires a faith that the furnaces can provide a return on investment, which is often much higher than for standard equipment.

nitrex.com

References:

- Tapar, O., Epp, J., et al., “In -Situ Synchrotron X-ray Diffraction Investigation of Microstructural Evolutions During Low-Pressure Carburizing.” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, Volume 52A, April 2021, pgs. 1427-1442.

- Korecka, E., Korecki, M., et al., “Calculation of the Mixture Flow in a Low-Pressure Carburizing Process,” Metals 2019, 9-2019, p. 439.

- Herring, D., “A Case for Acetylene based Low Pressure Carburizing of Gears,” Thermal Processing, 9-2012, pgs. 40-45.

- Hemsath, M., Herring, D., “The Future of the Integral Quench Furnace,” ASM Heat Treat Conference Proceedings, 2019.

- Hemsath, M. “CFC Fixtures Increase Productivity in Carburizing, Nitriding, and FNC”, Gear Technology, March/April 2021.

- 6. Cronite Group, “CFC/Alloy Hybrid — The Next Generation Solution.” The Monty website (www.themonty.com), August 2020.

- Herring, D., “A Layman’s Guide to Understanding the Theory of Gases,” HeatTreatToday.com, Best of the Web, 2014 (original 2014).

- Herring, D., “Technology Evolution of the Integral-Quench Furnace,” Industrial Heating, January 2020.