Research Objective and Approach

The research objective for generating

gear grinding at WZL is the increase of

process efficiency and process reliability

in generating gear grinding by description

of the technological cause-effect

relationships for cutting forces as well

as for occurrence of grinding burn in a

model. For the analysis of the cause-effect

relationships an analogy trail has been

developed and will be introduced in this

report.

The aim of this report is to present a

model to predict grinding burn for generating

gear grinding. Therefore cutting

forces in analogy trails are measured and

the interactions between process parameters

and occurred grinding burn are

taken into account. The measured cutting

forces will be combined in an empirical

cutting force model. With the ability

to calculate the cutting force the heat

flow density towards the workpiece can

be estimated. With a comparison of the

heat flow density and the grinding burn

occurrence a critical heat flow density

that leads to grinding burn can be determined.

Thereby a model to predict grinding

burn can be derived. In conclusion

the prediction model will be transferred

onto generating gear grinding and will

be validated by generating gear grinding

trials.

Analogy trail for Generating Gear

Grinding

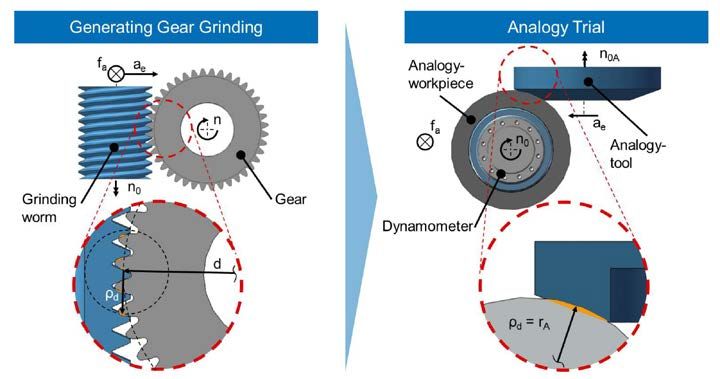

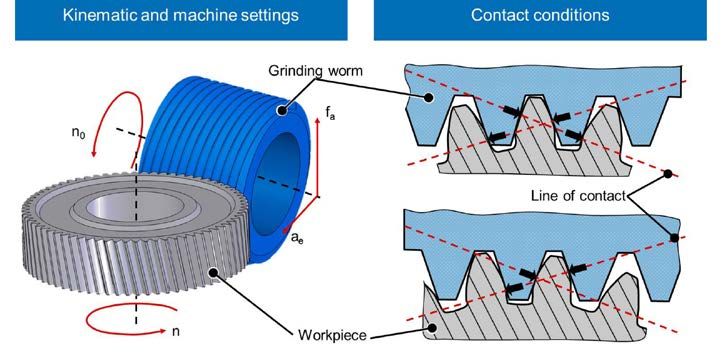

The complexity of the contact conditions

between tool and workpiece during

generating gear grinding complicates

the analysis of generating gear grinding.

On the one hand, the penetration volumes

change over the tooth profile height

during grinding. On the other hand, the

number of engaged tool flanks and workpiece

flanks is variable. To investigate

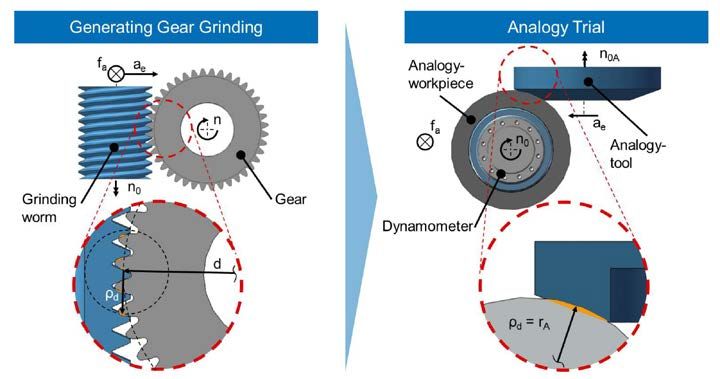

generating gear grinding on a single fixed

point on the tooth profile, a geometrickinematic

model, the analogy trail, has

been developed (Refs. 12, 9). The principle

of the analogy trail for generating gear

grinding is shown (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Analogy trial for generating gear grinding: principle and deduction of analogy

workpiece geometry (Ref. 9).

For each point of the involute the local

radius of curvature ρy can be calculated

(Ref. 13). For the analogy trail the contact

conditions at different positions of the

involute can be approximated. The radius

of the workpiece in the analogy trail

rA equals the radius of curvature at the

investigated point of the involute profile.

Thus the diameter of the analogy workpiece

depends on the number of teeth z,

the module mn, the helix angle β and the

pressure angle αn of the mapped sample

gear. The rack profile of the grinding

worm can be approximated in the investigated

contact point by a face wheel with a

conic working surface (Ref. 9).

Besides the workpiece and the tool

geometry the chip geometry in the analogy

trail has to be comparable to the chip

geometry in generating gear grinding.

Therefore the cutting length lcuA and the

chip thickness hcuA have to be comparable

between analogy trail and generating gear

grinding.

Furthermore the kinematics of chip

formation and the velocities must be fitted

to generating gear grinding. During

chip formation the lateral sliding speed

vtA, the axial feed speed vaA and the cutting

speed vc interfere with each other.

The cutting speeds in generating gear

grinding and analogy trail are the same.

The lateral sliding speed vtA can be calculated

by the rotational speed nA of the

workpiece and the requirement to be

synchronous. The axial feed speed vaA

can be adjusted according to the generating

gear grinding process as the product

of rotational speed nA and axial feed fa.

Rotational speed as well as axial feed in

analogy trail and generating gear grinding

is identical. The tool is a grinding

wheel with an angled surface. The angle

corresponds to the pressure angle αn0 of

the grinding worm.

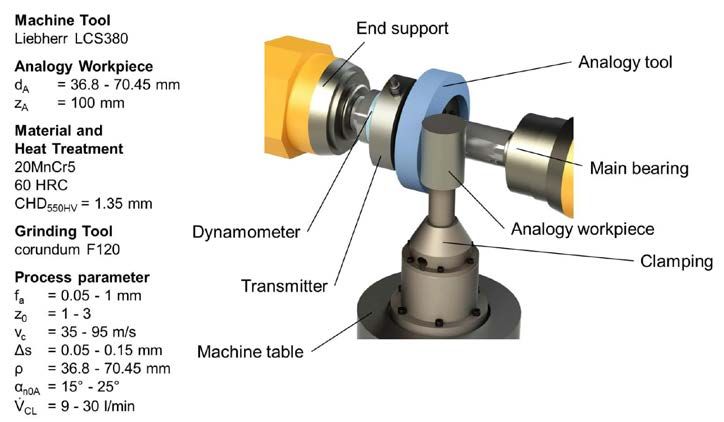

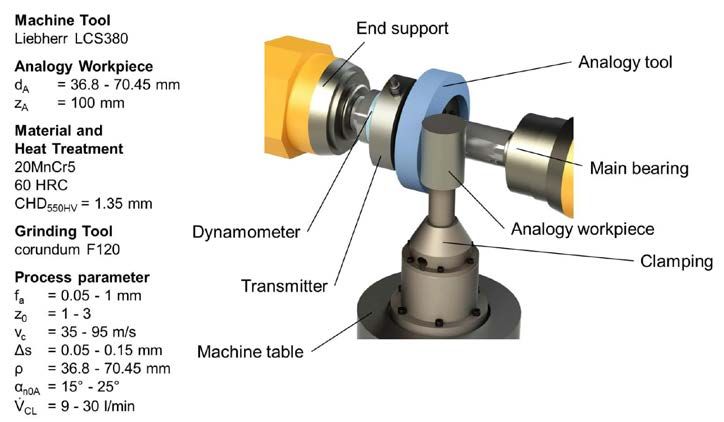

The mapped grinding process and the

machine tool used are shown (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Workpiece data and machine tool.

The mapped grinding process is carried

out with a spur gear with a number of

teeth of z = 31 and a normal module of

mn = 4.5 mm. The material is 20MnCr5.

The gears are case-hardened with a surface

hardness of 60 HRC and a case-hardening-

depth of CHD550HV = 1.4 mm.

The material and heat treatment of the

analogy workpieces match the spur gears.

All generating gear grinding and analogy

trails were performed on a model

LCS380 grinding machine from Liebherr-

Verzahntechnik GmbH that can perform

both generating and profile gear grinding.

For both analogy and generating gear

grinding trials, corundum tools with a

grain size F120 (average grain diameter

109 μm) from Winterthur Technology

AG are used.

The experimental set-up of the analogy

trails is shown (Fig. 4);

Figure 4 Experimental set-up analogy trial generating gear grinding.

the cutting force

can be determined with a dynamometer

which is integrated in the flow of forces.

For further information, a full description

of the analogy trail design can be

found in (Ref. 12).

With this experimental set-up, 129

analogy trails were performed. In these

analogy trails the following process

parameters were taken into account. The

axial feed fa, the number of starts z0, the

cutting speed vc, the stock Δs, the pressure

angle of the analogy tool αn0A and

the cooling lubricant volume flow VCL.

In addition, the diameter of the analogy

workpiece was varied to investigate different

points on the involute profile.

Prediction Model for Surface

Zone Inducements

Based on the empirical data of the analogy

trails an empirical-physical model

is built up in the following. Using the

model, the occurrence of a process-related

damage of the surface zone can be

predicted. For this purpose, an approach

to describe the surface zone inducement

is presented. Subsequently the required

parameters are determined and the prediction

model is derived.

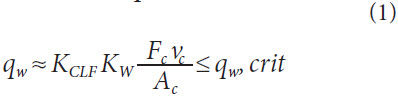

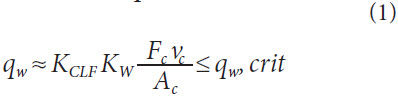

Analytical model approach. To predict

the surface zone inducement the heat

flow density, which describes the energy

flow in the contact zone between tool and

workpiece, must be determined. To prevent

grinding burn the heat flow density

towards the workpiece qw must always be

lower than a critical heat flow density qw,

crit that leads to a detrimental influence on

the surface zone.

The heat flow density towards the

workpiece qw corresponds to the current

energy flow through the contact area

between tool and workpiece Ac. In general

for grinding the majority of the cutting

energy is thermal energy, which is

produced by intense friction, shear and

separation processes as well as by friction

of the abrasive grain and bond (Ref.14).

Assuming that also for generating gear

grinding almost all cutting power is converted

into thermal energy, the total energy

flow in the contact area can be calculated

by the product of cutting force

Fc and cutting speed vc. In order to estimate

the heat flow density towards the

workpiece qw correction factors must take the distribution of the heat flow from the

contact zone into account. These corrections

factors are KCLF which takes into

account the cooling lubricant flow and

KW which considers the heat flow towards

the workpiece. With these factors the heat

flow density towards the workpiece qw can

be estimated with Equation 1(Ref. 15) as:

Determination of model parameters.

In the following, the correction factors

KCLF and KW, the cutting force Fc and the

contact area between workpiece and tool

Ac must be determined to calculate the

heat flow density. With correlation of the

known heat flow density and the occurrence

of grinding burn for every trial the

critical heat flow density can be determined

Cutting Force

The cutting force was measured during

the analogy trails with a dynamometer.

During the analogy trails various process

parameters were investigated to get

a statement about the influence on the

cutting force. In order that the cutting

force does not have to be determined

empirically for each combination of process

parameters, a cutting force model is

derived in the following.

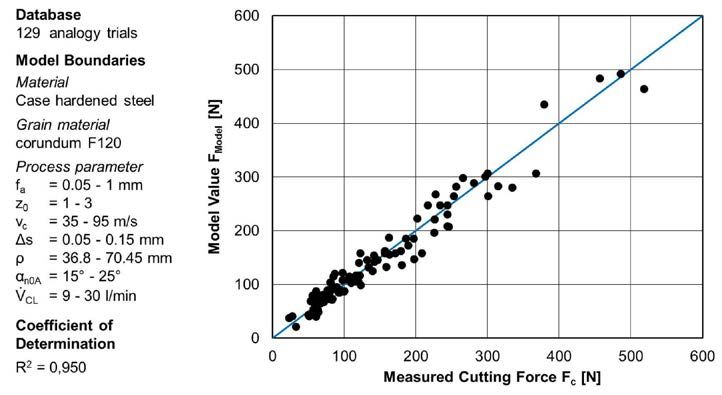

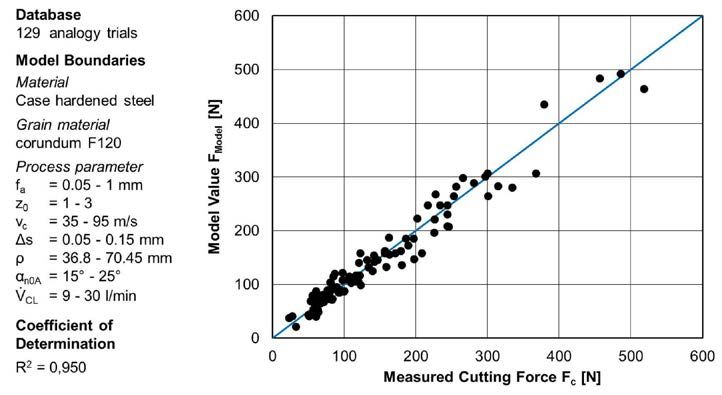

The cutting force model is set up based

on the obtained data from the analogy

trails using a regression analysis. For

regression analysis, the influence of the

process parameters axial feed fa, number

of starts z0, cutting speed vc, stock

Δs, cooling lubricant flow VCL and tool

pressure angle αn0A are considered. The

regression analysis of the cutting force is

carried out with a cubic approach considering

the interactions. For regression

analysis, the significance level was set to

α = 0.05. The comparison of the calculated

forces using the force model and

the measured forces is shown (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 Model results and observations of the cutting force.

Good correlation between calculated and

measured forces is evident; this is confirmed

by a coefficient of determination

of R2 = 0.950.

In summary it can be stated that the

cutting force model maps the measured

cutting forces very well and offers a high

stability due to a widely varying database.

Thus, the cutting force model is suitable

as a basis for calculating the heat flow

density and to derive a prediction model

for surface zone changes for generating

gear grinding.

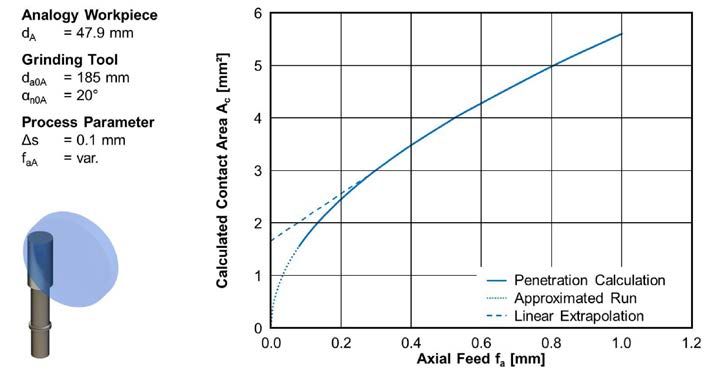

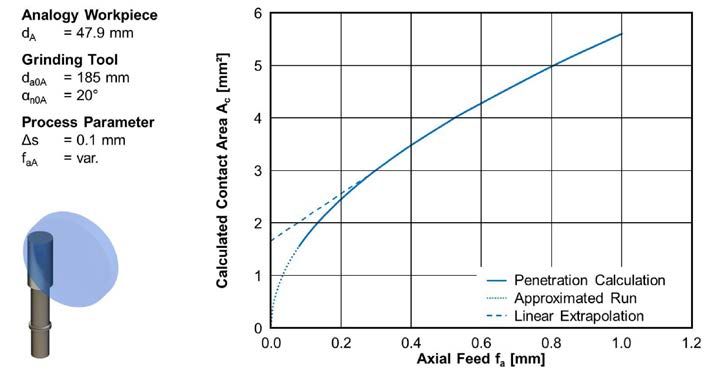

Contact Area

To define the heat flow density the contact

area between tool and workpiece

must be calculated. The contact area

Ac between tool and workpiece is corresponding

to the zone of heat transfer

between tool and workpiece. The contact

area for the analogy trails can be calculated

with a penetration calculation considering

various stocks and axial feeds.

Figure 6 shows the contact area for a constant

pairing of tool and workpiece over

axial feed. For an axial feed of fa < 0.2 mm,

the contact area drops sharply. For an

axial feed of fa < 0.08 mm no penetration

volume between workpiece and tool

could be calculated with the penetration

calculation.

Figure 6 Determination of contact area.

Due to numerical inaccuracies, the calculated

contact area for small axial feeds

is not exact. From kinematics it can be

derived that in the absence of axial feeding

a contact between tool and workpiece

must exist for the first rotation of tool

and workpiece. The contact area for low

axial feeds of fa < 0.25 mm is calculated

from an axial feed by linear extrapolation.

The extrapolated contact area is indicated

by the dotted line in the diagram. Using

this functional relationship, the contact

area Ac can be determined for the prediction

model.

Correction Factors

Finally, the two correction factors to

calculate the heat flow density must be

determined. The heat distribution for

each combination of tool, workpiece and

cooling lubricant is different and variable

over the contact zone (Ref. 16). Due to

the different thermal material parameters

such as specific heat capacity cp and thermal

conductivity λ, as well as the inability

to determine the temperatures in the con-

tact zone, the heat distribution factor KW

cannot be calculated for generating gear

grinding. In several studies heat distribution

factors have been estimated for different

grinding processes (Refs.17–22).

The evaluation of these papers shows that

up to 80% of the thermal energy can flow

into the workpiece. For surface grinding

of unhardened steel a heat distribution

factor KW = 0.65 was determined (Ref. 19).

A heat distribution factor for grinding of

hardened 20MnCr5 cannot be found in

the literature. Because of the poor accessibility

of the contact area during generating

grinding a heat distribution factor

KW = 0.8 is assumed in this work. This

corresponds to the standard assumptions

in literature and provides an assessment

on the safe side (Refs. 23–24).

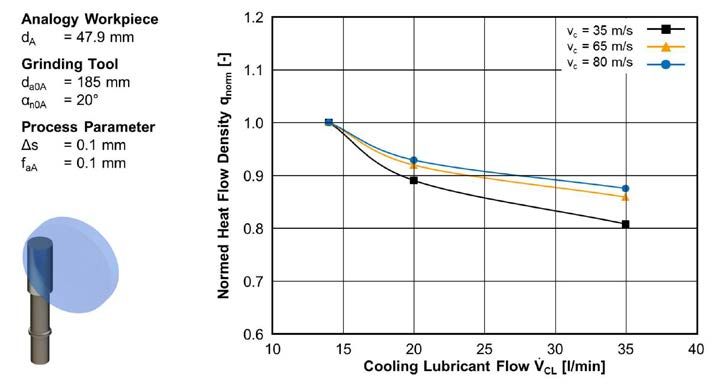

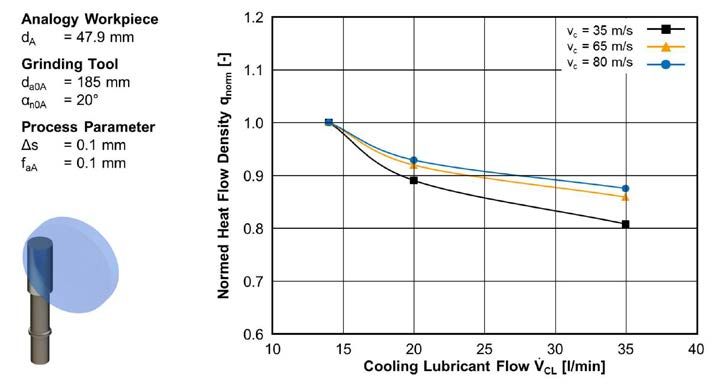

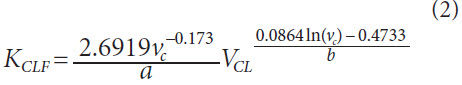

In addition to the constant heat distribution

factor KW, a variable factor KCLF

to determine the influence of the cooling

lubricant flow is necessary. For this purpose,

the heat flow densities of the analogy

trails were normalized to the maximum

heat flow density and analyzed

in relation to the cooling lubricant flow.

Using a regression analysis the influence

of the cooling lubricant flow on the heat

flow density was determined.

The normalized heat flow density qnorm

at constant process parameters decreases

with increasing cooling lubricant flow

(Fig. 7).

Figure 7 Determination of correction factor for consideration of cooling lubricant.

This effect is based on the better

supply of the contact area with cooling

lubricant. With increasing cutting

speed, the influence of the cooling lubricant

flow decreases. The rotation of the

tool produces a flow of air, which deflects

the coolant. The higher the cutting speed

the greater the cooling lubricant is dispersed

and the worse the contact area is

supplied with cooling lubricant (Ref. 6).

Therefore, the correction factor for the

cooling lubricant, which represents the

influence of the cooling lubricant flow on

the heat flow, is dependent on the cutting

speed vc as well.

For constant cutting speeds, the heat

flow towards the cooling lubricant can

be approximated by an exponential function

depending on the cooling lubricant

flow VCL. The correction factor KCLF can

be described by Equation 2. The factors

a and b were determined as a function of

cutting speed using regression analysis.

The coefficient of determination for the

equation of the correction factor KCLF is:

The energy flow towards the workpiece

can be estimated by the product of the

two correction factors KW, KCLF and the

cutting power. Depending on the cutting

speed and cooling lubricant flow, the percentage

of the energy flow towards the

workpiece is between 60% and 80% of the

total cutting power.

Empiric analytical prediction model.

Based on the empirical knowledge of cutting

force and the analytical considerations

of an analytical heat flow density

an empirical-analytical prediction model

is derived in the following. The model is

used to predict the process-related influences

on the surface zone taking into

account the heat flow density towards the

workpiece.

Using the presented empirical force

model and the mathematical description

of the model parameters, the heat flow

density can be calculated for every trial.

In addition to the magnitude, the residence

time of the heat flow density also

has a major impact on the influence on

the surface zone. The residence time of

the heat flow density for one point on the

surface equals the contact time tc between

tool and workpiece for the same point.

The contact time for generating gear

grinding can be calculated with Equation

3, (Ref. 25).

As with tool and process variables, the

contact time is also dependent on the

workpiece geometry. The contact time is

calculated by the rotational speed of the

tool n0, the number of starts z0, the number

of teeth of the workpiece z and the rolling angle of the cutting width Δφc.

The rolling angle describes the required

arc segment, which must be passed in

order to achieve the width of contact

between tool and workpiece at the

respective profile point.

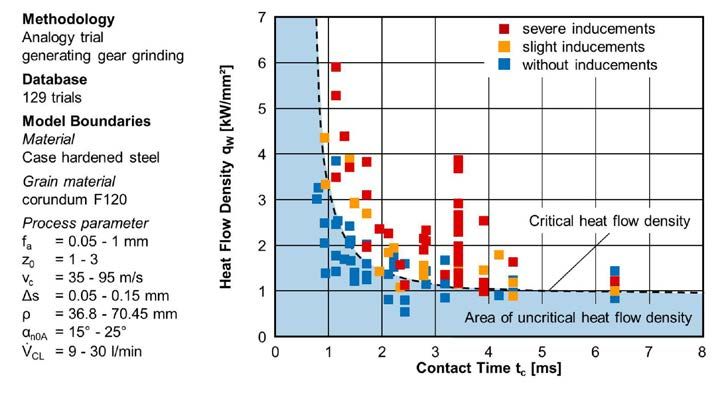

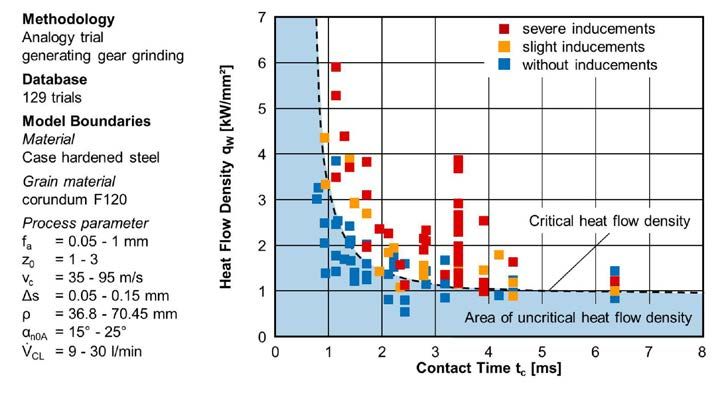

For the analogy trails, the heat flow

density is plotted against the contact time

(Fig. 8).

Figure 8 Surface zone inducements depending on heat flow density.

For this purpose, the heat flow

density was calculated for each point of

the analogy trails. The workpieces from

the analogy trails are marked in different

colors according to the type of influence

on the surface zone. Points that have

been highlighted in yellow and red show

a slight to strong influence on the surface

zone of the analogy workpiece. Points

marked in blue represent non influenced

surface zones. As a detection method

nital etching was used. For disposition of

detrimental surface zone inducements an

additional quantitative damage classification

was performed using the measurement

of Barkhausen noise.

The analysis shows that for a short contact

time a high heat flow density can

flow into the workpiece without causing

damage. In contrast, at long contact

times only a low heat flow density is necessary

to harm the surface zone. With

increasing contact time, the critical limit

asymptotically approaches a constant

level. From this distribution, the contact

time depending limit of the critical heat

flow density can be determined from the

graph and described mathematically.

The calculated critical heat flow density

is shown as a black dashed line in

the graph. Considering the simplified

assumptions for the calculation of the

correction factors as well as the contact

time and the dispersion of results, a very

well approximation for determining the

critical heat flow density can be found.

In summary it can be stated that the

empirical-analytical model is suitable to

determine the critical limit, which leads to

grinding burn. However, it must be determined

whether the model, which is based

on analogy trail results, can be applied to

actual generating gear grinding. For this

purpose, the prediction model must first

be validated with the sample gear that is

mapped in the analogy trail.

Validation of the Prediction

Model

The prediction model constructed on

basis of analogy trails is compared and

validated in the following with results

from generating gear grinding trials.

First, the transferability of the model to

generating gear grinding is validated. For

this purpose grinding tests are carried

out with the sample gear that is mapped

in the analogy trail. Subsequently, the

model is validated on an additional gear.

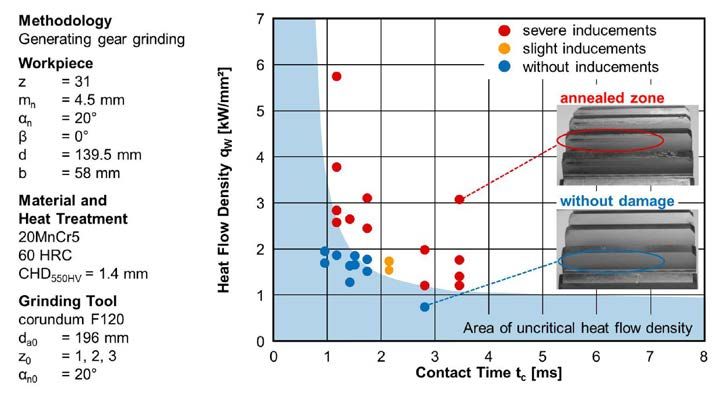

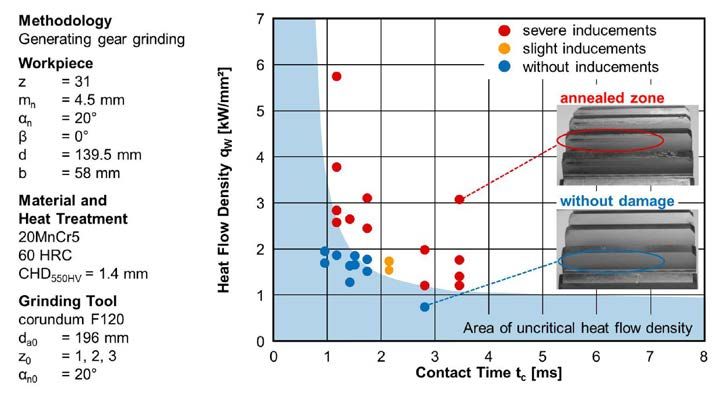

Transfer to generating gear grinding.

For the validation of the prediction

model a deductive approach is chosen

in the following. The general model was

applied to a particular case to validate the

findings. For the gear that is mapped in

the analogy trail, the heat flow densities

have been calculated for each set of process

parameters. The classification of heat

flow densities and surface zone inducements

in the analytical empirical prediction

model is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9 Model validation for sample gear.

The results of generating gear grinding

trials were arranged in the characteristic

field of the heat flow density of the prediction

model. The heat flow densities

shown are calculated for the pitch circle

diameter of the sample gear. The degree

of influence on the surface zone has been

marked in analogy to the previous illustrations.

The range of non-critical heat

flow density is identical due to the geometric

relationship between analogy trail

and sample gear.

All points for which no detrimental

surface zone inducement was observed

after generating gear grinding are with

one exception within the non-critical

area. The heat flow densities of the components

with slight and severe detrimental

inducements are larger than the calculated

critical heat flow density of the prediction

model.

The evaluation shows that the prediction

model is able to predict the occurrence

of grinding burn in good accuracy

for the sample gear. The results of the

generating gear grinding trials reflect the

determined findings and identified relationships

from the analogy trail. Thus,

the prediction model has been validated

for the sample gear. Whether the prediction

model can be applied to additional

gears must be examined in the following.

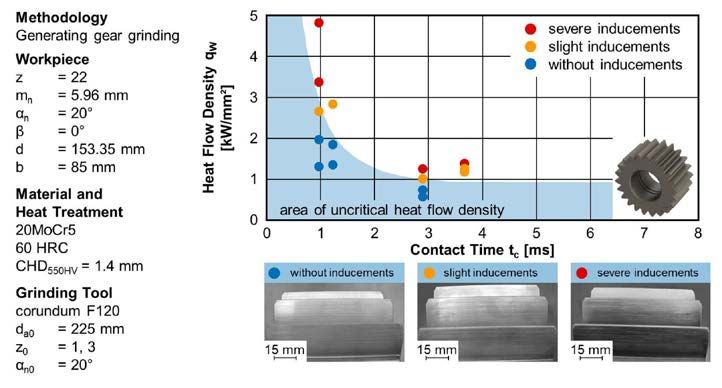

Validation with additional gears. In

order to test the transferability of the

empirical-analytical prediction model,

the model is applied to another spur gear.

Therefore further generating gear grinding

trials were performed.

The design of experiments was defined

by using the prediction model. For this,

the process parameters were predicted

for both clearly damaged and not affected

tooth flanks. The gears have been

inspected after grinding by means of nital

etching to evaluate and document surface

zone inducements.

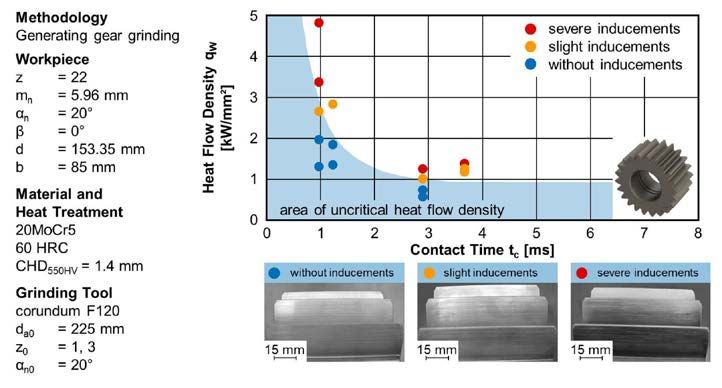

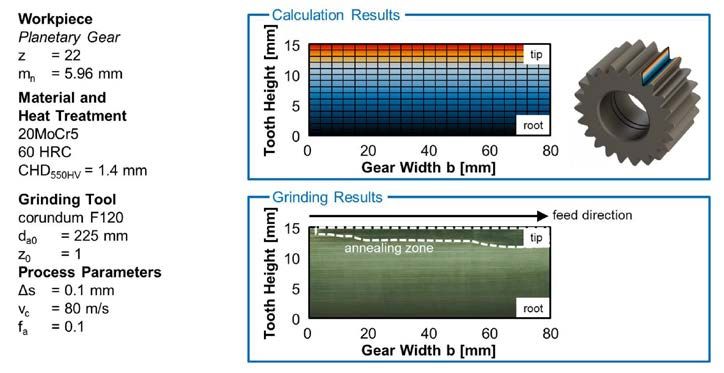

As a second application a planetary

gear of a construction machine is selected.

In contrast to the previous gear, the

present gear has a higher module and a

higher face width. The gear geometry and

further details of material and heat treatment

can be found in Figure 10.

Figure 10 Gear geometry of planetary gear.

The results of the second gear geometry

are shown (Fig. 11);

Figure 11 Application of prediction model for planetary gear.

for these trials tools

with different number of starts were used.

The calculated critical heat flow density

for the pitch circle diameter limits the

damaged and non-damaged gears with a

good accuracy. Different forms of surface

zone inducements are shown in the lower

part of Figure 11. All workpieces with a

detrimental inducement show a damaged

zone near the tip area.

Severely damaged components show

a dark coloration over a large part of

the profile. In addition to the qualitative

statement about whether surface zone

damage is to be expected, the heat flow

density can be calculated on the basis of

the local approach for any point of the

gear flank.

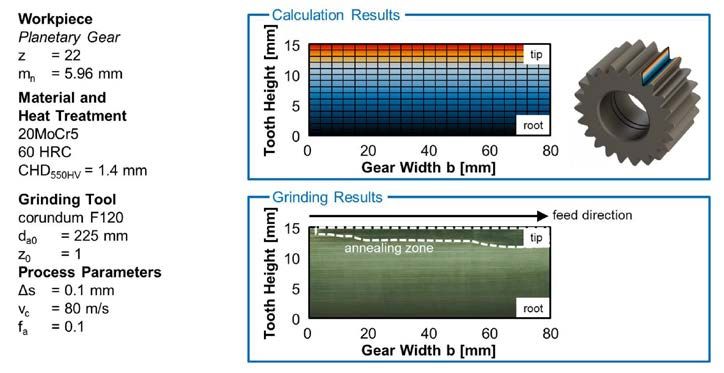

To explain the process-related detrimental

inducement in the tooth tip area,

the distribution of the heat flow density

has been calculated for a process design

for the entire tooth profile. The results

are compared with results of nital etching

in Figure 12.

Figure 12 Comparison of local heat flow density and process results.

The occurrence probability of a surface

zone inducement is marked in color

on the tooth height. In the black and blue

areas no surface zone inducement is to be

expected. In the transition between the

light blue and the yellow area there may

be a slight damage. In the tooth tip area,

the critical heat flow density is exceeded

and therefore a damaged surface zone is

expected. This area is marked in red.

The distribution over the tooth height

can be explained by the cause-effect relationships,

determined in the analogy

trails. With an increase in the radius of

curvature the cutting forces increase as

well. This results in a varying heat input

over the tooth profile. The highest cutting

force and therefore the largest heat flow

density on the tooth flank is present at

the tooth tip. This result is well-correlated

with the results of nital etching.

In feed direction the affected zone is

growing in contrast to calculation results.

The main reason for the expansion of

the damaged zone is wear of the grinding

worm. With increasing machining

time also the friction and therefore the

cutting force as well as the heat flow density

increases. In the prediction model the

wear of the grinding wheel is not taken

into account. For this reason, predicted

and actual damage differ.

By applying the predictive model to an

additional gear, the applicability was tested

for other geometries. It turns out that

the prediction model derived from the

analogy trail can also be used to predict a

detrimental inducement of the surface for

additional geometries.

Summary and Outlook

The thermo-mechanical surface zone

inducement is an important quality criterion

for functionality of gears. Also for

generating gear grinding it is necessary to

determine thermal and mechanical loads

and their influencing factors to avoid

damage of the surface zone.

The research objective of this report

was to derive a model to describe and

predict detrimental surface zone inducements

for generating gear grinding.

Therefore, the necessary model parameters

and correction factors were determined.

Subsequently, the model was validated

using two gear geometries.

The objective of this report was met

through validation of the predictive

model. The model for predicting detrimental

surface zone inducements will

help increase the efficiency and process

reliability of continuous generating gear

grinding and improve the description

and understanding of the technological

cause and effect relations.

In the next step the derived empirical

analytical prediction model should be

linked with a manufacturing simulation.

The combination of a local determination

of chip geometries and the automated

calculation of the existing model

parameters will allow widespread use

of the model in industrial applications.

Furthermore, it will significantly improve

the process design and optimization in

continuous generating gear grinding. In

addition, the cutting force model can be

extended with a link to a manufacturing

simulation. With the help of calculated

chip geometries it is likely possible to find

a correlation between chip geometries

and the measured cutting forces.

Besides the optimization of the model

a further development of the analogy

trail is possible. With the analogy trail, an

evaluation of the performance of grinding

worms for generating gear grinding

can be performed. So on the one hand, a

pre-selection of grinding worm specifications

is possible and on the other hand the wear behavior could be analyzed better

due to the simple geometry of the

grinding tool.

Dipl.-Ing. Matthias

Ophey studied mechanical

engineering at RWTH Aachen

University with a focus on

production engineering.

Upon graduation in 2013 he

became a scientific research

assistant in the gear

department of the Laboratory of Machine Tools

and Production Engineering (WZL). Ophey’s

research is dedicated to focusing on hard

finishing of gears — especially generating gear

grinding, and manufacturing-related properties.

Dr. Jan Reimann is a 2008

graduate of RWTH Aachen

University, having studied

mechanical engineering

with a focus on production

engineering. He began

working in 2008 — first

as scientific research

assistant and later as

team leader — in the gear department of the

Laboratory of Machine Tools and Production

Engineering (WZL). While there he has

published his doctoral thesis on generating

gear grinding. Today Reimann is a production

engineer at Siemens Mechanical Drives in

Bocholt, focusing on manufacturing technology

development.

References:

- Schlattmeier, H. Diskontinuierliches

Zahnflankenprofilschleifen mit Korund,

Dissertation, RWTH Aachen, 2003.

- Meijboom, L. Erhöhung der Wirtschaftlichkeit

beim Wälzschleifen durch Verbesserung des

Zerspannvorgangs, Dissertation,

RWTH Aachen, 1979. 3. Türich, A.

Werkzeugprofilerzeugung für das

Verzahnungsschleife, Dissertation, Universität

Hannover, 2002.

- Bausch, T., Moderne Zahnradfertigung.

Verfahren und Maschinen zur kostengünstigen

Herstellung von Stirn- und Kegelrädern mit hoher

Qualität, 3. Auflage, Expert Verlag, Renningen-

Malmsheim, 2006.

- Stimpel, F.Technologische Kenngrößen

für das kontinuierliche Wälzschleifen von

Evolventenverzahnungen, Dissertation,

Universität Hannover, 2009.

- Klocke, F. and König, W., Fertigungsverfahren

Band 2: Schleifen, Honen, Läppen. 4. Auflage,

VDIVerlag, Düsseldorf, 2005.

- Reichel, F. Verfahrensauswahl beim Schleifen von

Großverzahnungen, Seminar: Feinbearbeitung

von Zahnrädern, WZL der RWTH Aachen,

November 2007.

- Sulzer, G. Werkzeugmaschinen zum

Feinbearbeiten der Zahnradflanken von vorverzahnten

Zahnrädern, Europäische Patentschrift

EP0282046, Liebherr Verzahntechnik, Kempten,

1993

- Klocke, F., C. Gorgels, and J. Reimann.

Generating Gear Grinding – New Possibilities

in Process Design and Analysis, AGMA Fall

Technical Meeting 2011, 11FTM02, ISBN 978-1-

61481-001-8.

- Klocke, F., C. Gorgels and J. Reimann. Analyse

des kontinuierlichen Wälzschleifens mithilfe der

Durchdringungsrechnung, In: 50. Arbeitstagung

„Zahnrad und Getriebetechnik“, Hrsg.: Klocke,

F.; Brecher, C., Eigendruck Getriebekreis

Aachen, S.14-1 - 14-40, 2009.

- Klocke, F., C. Gorgels and J. Reimann.

Kontinuierliches Wälzschleifen von Verzahnungen

– Softwareunterstützte Prozessoptimierung, In:

WB Werkstatt und Betrieb, Jg. 142, Heft 5, S.62-

63, 2009.

- Klocke, F., C. Gorgels and J. Reimann. Ansatz

für ein Prozesskraftmodell für das kontinuierliche

Wälzschleifen von Verzahnungen, In: 51.

Arbeitstagung „Zahnrad und Getriebetechnik“,

Hrsg.: Klocke, F.; Brecher, C., Eigendruck

Getriebekreis Aachen, S.8-1 - 8-40, 2010.

- DIN 3960. Begriffe und Bestimmungsgrößen für

Stirnräder (Zylinderräder) und Stirnradpaare

(Zylinderradpaare) mit Evolventenverzahnung,

Hrsg. Deutscher Normenausschuss, März 1987.

- Vits, R. Technologische Aspekte der

Kühlschmierung beim Schleifen, Dissertation,

RWTH Aachen, 1985.

- Takazawa K. Effects of Grinding Variables on

Surface Structure of Hardened Steel, In: Bulletin

of the Japan Society of Grinding Engineers,

Volume 2, S. 14-21, 1966.

- Hoffmeister, H.-W and B. Denkena. Jahrbuch

Schleifen, Honen, Läppen, Polieren: Verfahren

und Maschinen, Vulkan-Verlag, Essen, 63.

Ausgabe, ISBN 3-802-72941-2, Oktober 2007.

- Gorgels, C. Entstehung und Vermeidung

von Schleifbrand beim diskontinuierlichen

Zahnflankenprofilschleifen, Dissertation, RWTH

Aachen, 2011.

- Grof, H.E. Beitrag zur Klärung des Trennvorgangs

beim Schleifen von Metallen, Dissertation, TU

München, 1977, 15 14FTM02.

19. Hoffmeister, H.-W. and H.K. Tönshoff. Jahrbuch

Schleifen, Honen, Läppen, Polieren: Verfahren

und Maschinen, Vulkan-Verlag, Essen, 61.

Ausgabe, 2004.

- Lowin, R. Schleiftemperaturen und ihre

Auswirkungen im Werkstück, Dissertation,

RWTH Aachen, 1980.

- Rowe, W.B., S.C.E. Black, B. Mills, H.S. Qi and

M.N. Morgan. Experimental Investigation of

Heat Transfer in Grinding, In: Annals of the

CIRP, Volume 44/1/1995, S. 329-332.

- Steffens, K. Thermomechanik des Schleifens,

Dissertation, RWTH Aachen, 1983.

- Heinzel, C. Schleifprozesse verstehen: Zum

Stand der Modellbildung und Simulation sowie

unterstützender experimenteller Methoden,

Habilitation, Universität Bremen, 2008.

- Tönshoff, H.K., J. Peters, I. Inasaki and T. Paul.

Modelling and Simulation of Grinding Processes,

In: CIRP Annals 41(2):677–688, 1992.

- Schriefer, H., W. Thyssen, W., Wirz, G. Scacchi

and M. Gretler. Kontinuierliches Wälzschleifen

von Verzahnungen, 1. Auflage, Eigenverlag

Reishauer AG, Wallisellen, 2008.

Figure 1 Generating gear grinding: principle, machine settings, and contact conditions (Ref. 9).

Figure 1 Generating gear grinding: principle, machine settings, and contact conditions (Ref. 9). Figure 2 Analogy trial for generating gear grinding: principle and deduction of analogy

workpiece geometry (Ref. 9).

Figure 2 Analogy trial for generating gear grinding: principle and deduction of analogy

workpiece geometry (Ref. 9). Figure 3 Workpiece data and machine tool.

Figure 3 Workpiece data and machine tool. Figure 4 Experimental set-up analogy trial generating gear grinding.

Figure 4 Experimental set-up analogy trial generating gear grinding.

Figure 5 Model results and observations of the cutting force.

Figure 5 Model results and observations of the cutting force. Figure 6 Determination of contact area.

Figure 6 Determination of contact area. Figure 7 Determination of correction factor for consideration of cooling lubricant.

Figure 7 Determination of correction factor for consideration of cooling lubricant.

Figure 8 Surface zone inducements depending on heat flow density.

Figure 8 Surface zone inducements depending on heat flow density. Figure 9 Model validation for sample gear.

Figure 9 Model validation for sample gear. Figure 10 Gear geometry of planetary gear.

Figure 10 Gear geometry of planetary gear. Figure 11 Application of prediction model for planetary gear.

Figure 11 Application of prediction model for planetary gear. Figure 12 Comparison of local heat flow density and process results.

Figure 12 Comparison of local heat flow density and process results. Dipl.-Ing. Matthias

Ophey studied mechanical

engineering at RWTH Aachen

University with a focus on

production engineering.

Upon graduation in 2013 he

became a scientific research

assistant in the gear

department of the Laboratory of Machine Tools

and Production Engineering (WZL). Ophey’s

research is dedicated to focusing on hard

finishing of gears — especially generating gear

grinding, and manufacturing-related properties.

Dipl.-Ing. Matthias

Ophey studied mechanical

engineering at RWTH Aachen

University with a focus on

production engineering.

Upon graduation in 2013 he

became a scientific research

assistant in the gear

department of the Laboratory of Machine Tools

and Production Engineering (WZL). Ophey’s

research is dedicated to focusing on hard

finishing of gears — especially generating gear

grinding, and manufacturing-related properties. Dr. Jan Reimann is a 2008

graduate of RWTH Aachen

University, having studied

mechanical engineering

with a focus on production

engineering. He began

working in 2008 — first

as scientific research

assistant and later as

team leader — in the gear department of the

Laboratory of Machine Tools and Production

Engineering (WZL). While there he has

published his doctoral thesis on generating

gear grinding. Today Reimann is a production

engineer at Siemens Mechanical Drives in

Bocholt, focusing on manufacturing technology

development.

Dr. Jan Reimann is a 2008

graduate of RWTH Aachen

University, having studied

mechanical engineering

with a focus on production

engineering. He began

working in 2008 — first

as scientific research

assistant and later as

team leader — in the gear department of the

Laboratory of Machine Tools and Production

Engineering (WZL). While there he has

published his doctoral thesis on generating

gear grinding. Today Reimann is a production

engineer at Siemens Mechanical Drives in

Bocholt, focusing on manufacturing technology

development.