Gear mesh, NVH Evaluation

Ask the Expert

Gear Mesh

Question #1

When Assembling a pair of gears, what is a good method for setting and checking their mesh?

Expert response provided by: Dr. Robert Winfough and N.K. (Chinn) Chinnusamy (A previous answer to this question, written by Robert Wasilewski of Arrow Gear, appeared in the May 2015 issue).

The question is quite broad, as there are different methods for setting various types of gears and complexity of gear assemblies, but all gears have a few things in common.

When assembling spur or helical gears, backlash and contact pattern are important. Depending on the precision of the gear boxes, inspecting other items prior to assembly may also be wise. Before assembling high-speed gearboxes, all gears should be visually inspected to make sure there are no burrs or damage which will contribute to noise and premature wear. The gear housing should be CMM-inspected for center distance and alignment of bores to make sure they are within the tolerance specified. When multiple gear centers are involved, it is often difficult to check backlash; hopefully the gearbox design allows for inspection access. The backlash within each mesh should be checked along with contact pattern before assembling other gear centerlines. Bearing preload or controlled looseness are also important, depending on the speed. Of course, proper lubrication of gears and bearings should be considered for long gear and bearing life.

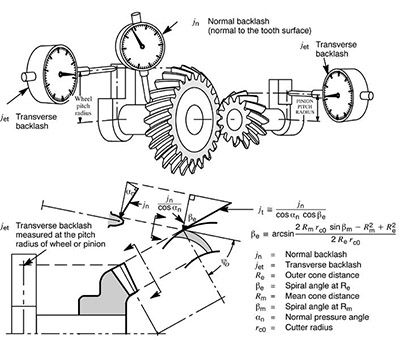

Bevel gears are generally manufactured as matched sets; individual members are not interchangeable between sets unless ground to a master. The quality of performance that is designed and manufactured into a set of bevel gears can only be achieved by correct mounting of gears at assembly. Gears assembled with improper mounting will wear excessively, operate noisily and possibly fail. Here again, checking the backlash and contact pattern should be done.

In assembling bevel gear (straight, spiral, and hypoid) the following must be observed.

Understanding of the need for correct positioning of bevel gears Inspection data necessary for correct assembly and positioning of bevel gears in the housing.