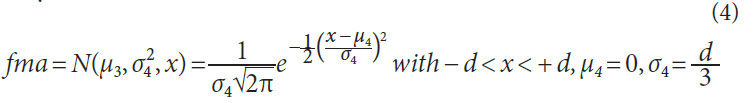

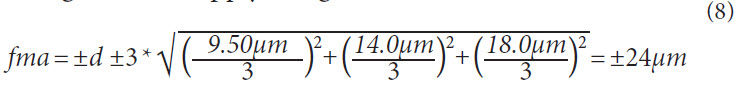

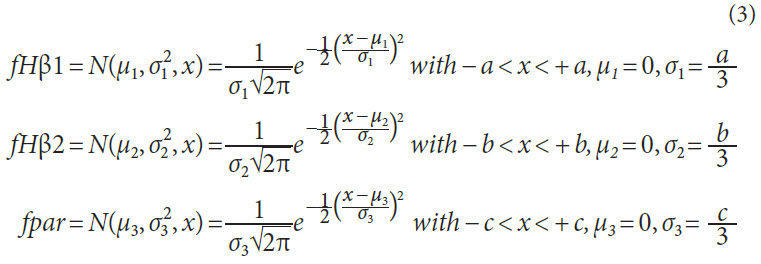

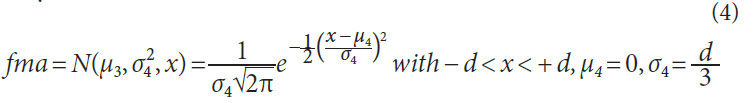

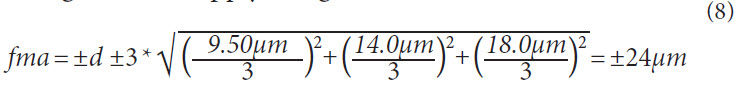

Also, we may express the resulting error, fma, as a probability

density function as follows:

Because fHβ1, fHβ2 and fpar are independent of each other,

we find the standard deviation σ4 as follows:

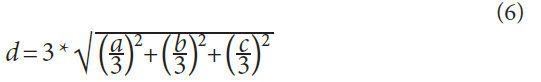

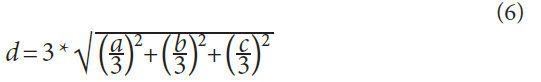

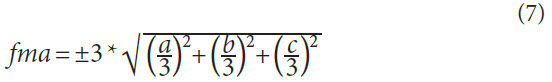

Again assuming that 3-Sigma rule applies for fma

(i.e. — d = 3*σ4) we find:

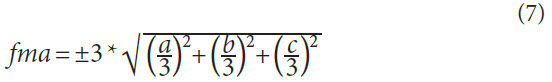

And

Which means that after assembly, 99.73% of all gearboxes

have a total misalignment of the flanks with respect to each other of fma = ±d — where d is calculated using the

above formula.

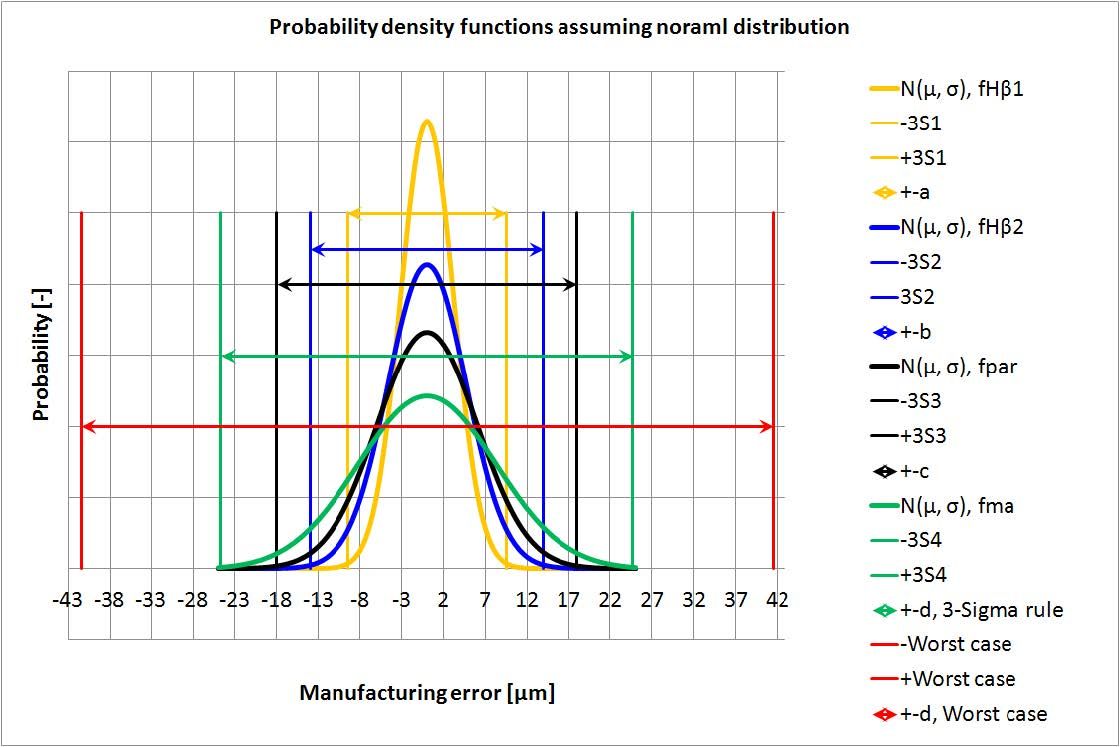

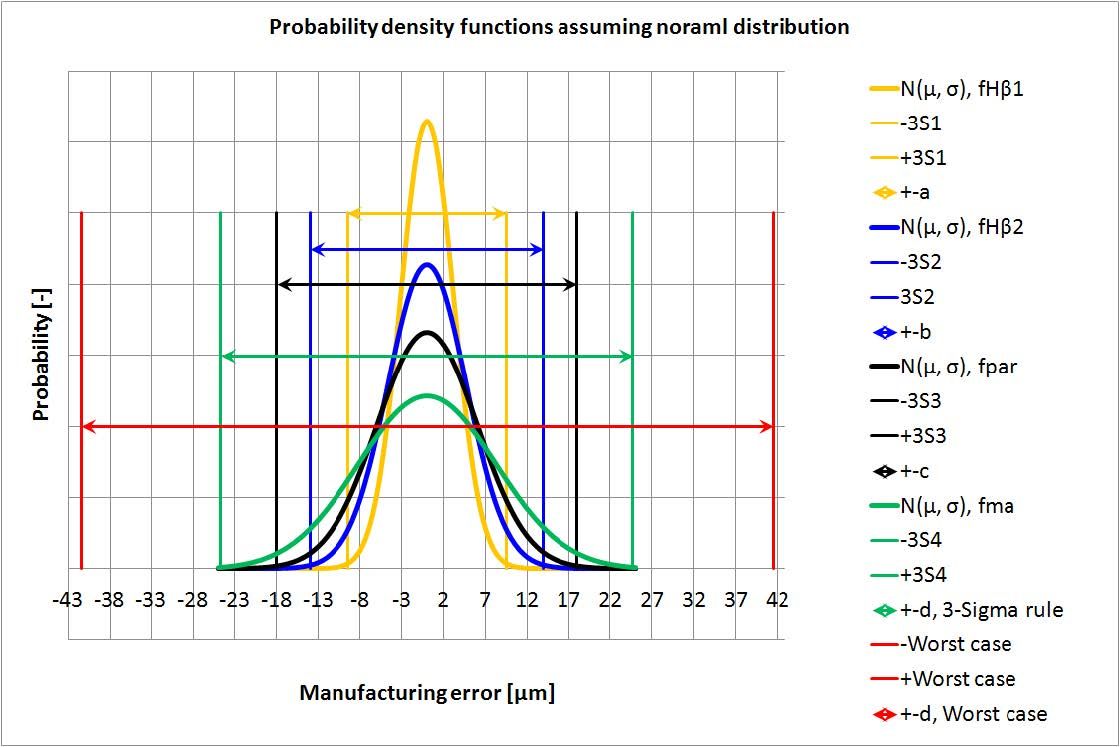

Figure 1 Normal distribution of manufacturing errors, resulting error, and worst-case scenario.

The above relationships are shown in Figure 1.

The probability density functions (assumed

to be normal distributions) of the three basic

errors — fHβ1, fHβ2 and fpar — are shown in

orange, blue and black. Also shown are the tolerances

±a, ±b, ±d corresponding to ±3*σ1, ±3*σ, ±3*σ3

(where σ is the standard deviation).

Combining these three random errors, we find the probability

density function (again assumed to be a normal distribution)

of the resulting error fma in green. Also shown is the tolerance

±d corresponding to ±3*σ4.

For comparison, the worst-case scenario where d = a + b + c is

shown in red.

We can clearly see that if we use the worst-case scenario, the

value for d is much higher than the value for d, were we to use a

statistical approach.

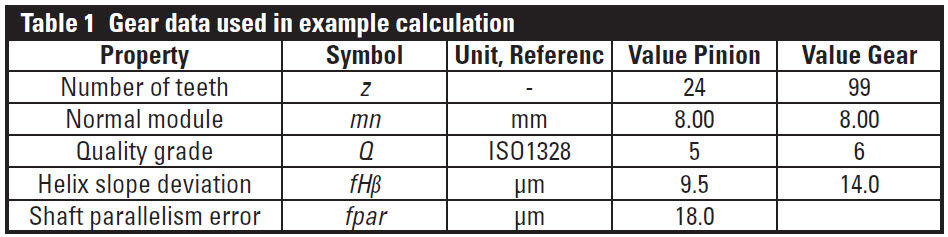

Applying the above formulas we find that the resulting tolerance

range ±d if we apply 3-Sigma Rule as:

And if we apply a worst-case scenario, we find:

Considering the above statement that the worst-case

approach is considered as overly conservative, then, for the

above gear pair, we would consider a random manufacturing

error in the mesh of fma = ±d = ±24.7μm, when calculating KHβ

along ISO6336-1, Annex E.

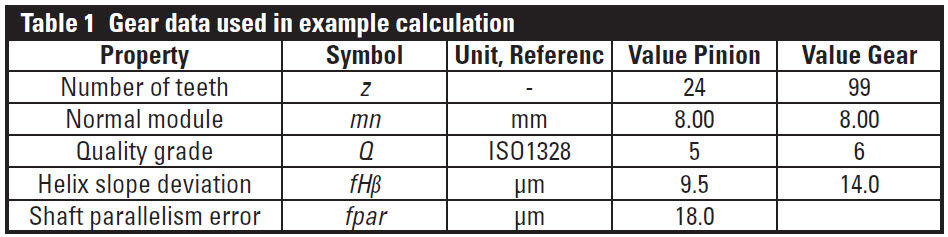

KHβ calculation using statistical or worst-case scenario for

fma. Let us consider again the above gear example. We apply

helix angle modifications on the pinion such that we compensate

the shaft bending, shaft torsion and bearing deformation.

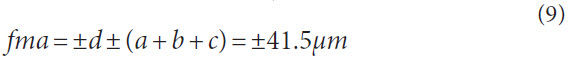

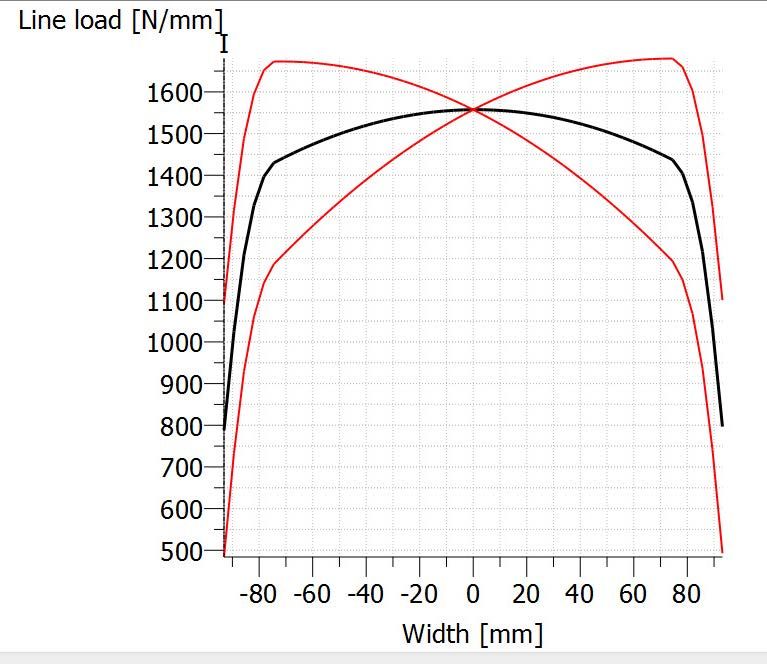

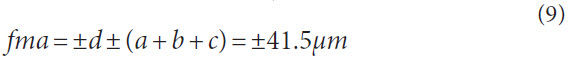

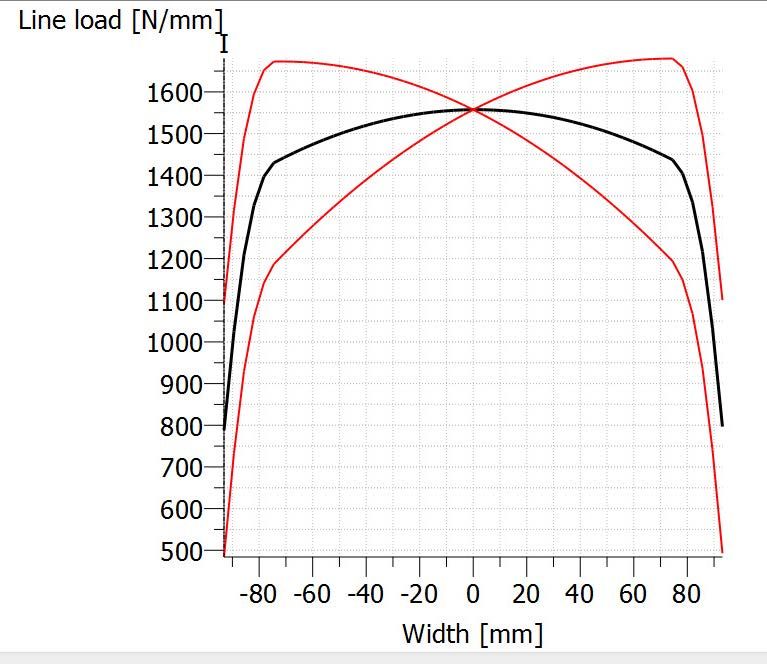

Figure 2 Line load distribution in the mesh for the example — not

considering any random manufacturing errors; KHβ = 1.08.

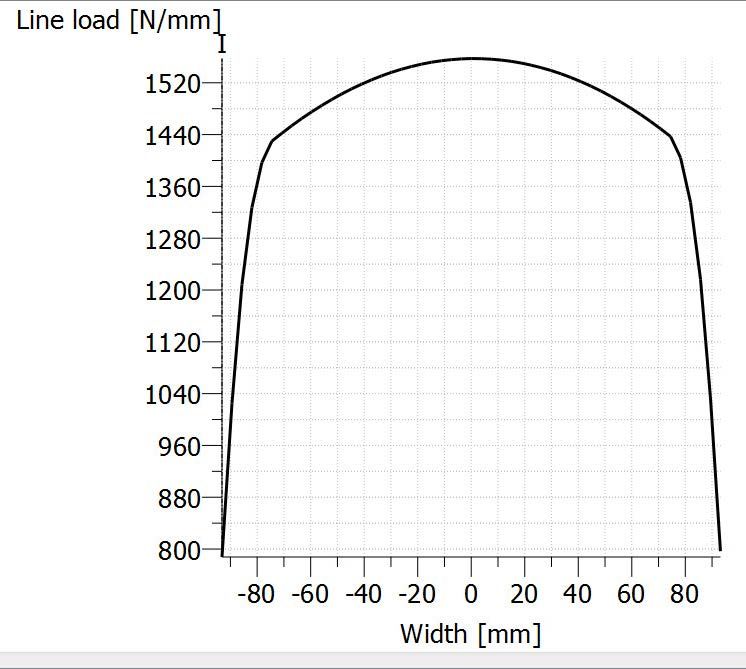

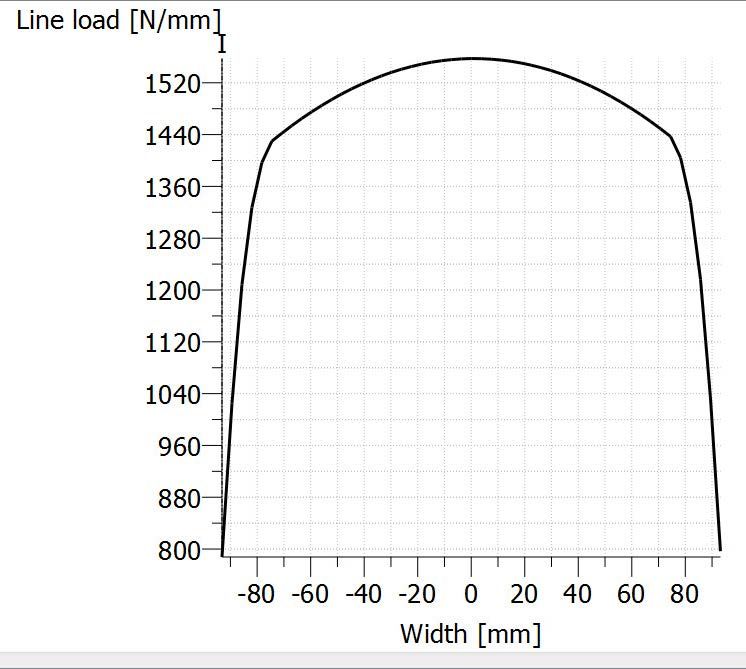

Figure 3 Line load distribution considering random manufacturing

errors fma = ±24.7μm (green lines); KHβ = 1.11; highest line load

occurs well within the crowned area of the face width; design

considered suitable.

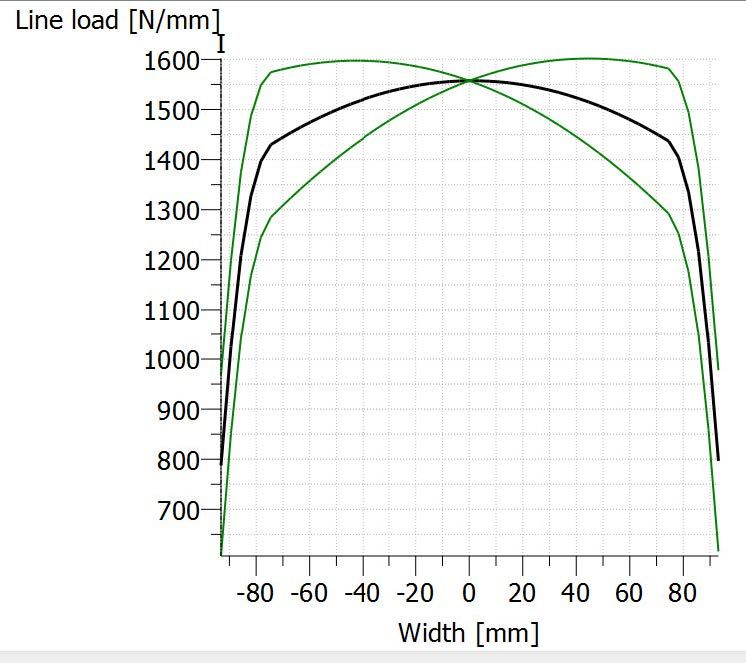

Figure 4 Line load distribution considering random manufacturing errors

fma = ±41.5μm (red lines); KHβ = 1.16; highest load occurs in

the transition area between crowning and end relief; design

considered as not suitable.

The result is a symmetrical line load distribution, calculated

along ISO6336-1, Annex E. If we ignore the random manufacturing

error (assuming fHβ1 = fHβ2 = fpar = 0.0μm), the load

distribution is then symmetrical and highest value lies in the

middle of the gear face width due to an applied crowning of

Cβ = 20μm. Let us also apply a curved end relief over 10% of

the gear face width per side; the amount is CβI = CβII = 45.0μm

(notations as per ISO21771 apply).

The resulting line load distribution is shown below, the

resulting face load distribution factor is KHβ = 1.08.

If we now consider the random manufacturing error

fma = ±24.7μm (from the 3 Sigma-Rule), we find three line

load distributions (one without manufacturing error, one using

fma = +24.7μm, and fma = −24.7μm), as shown below. The face

load distribution factor has now increased to KHβ = 1.11. And

yet, the highest line load remains within the crowned part of

the face width; thus the design would be deemed quite acceptable.

But if we consider the worst-case manufacturing

error — fma = ±41.5μm — we find the below line load distributions.

The face load factor is now KHβ = 1.16 and we find that

the highest line load is just where the end relief is about to start,

thus rendering the design unacceptable in this case.

Conclusion

Hans-Peter Dinner

Hans-Peter Dinner studied mechanical

engineering at the Swiss Federal Institute

of Technology (ETH), where during his

studies he spent time with Mercedes

Benz working on FEM of car bodies; with

Buhler in South Africa for training; and

with the National University of Singapore

for writing his thesis on FEM analysis

of medical devices. He began as an

FEM engineer, working with the leading

consultant in Switzerland on welded

structures, pressure vessels and satellite structures. Dinner later joined a

leading roller coaster design company, being responsible for all strength

verifications. He then moved on to KISSsoft AG, supporting customers in

the use of their gear software, working on gear optimization projects, and

ultimately transitioning to sales of KISSsoft products, with a focus on the

Asian market. In 2008 he started his own consultancy firm, EES KISSsoft

GmbH, sharing his time between KISSsoft support and sales in Asia and

project work. Key projects included design and testing of SCD3MW and

SCD6MW wind gearboxes, and large-bearing calculations for cranes and

wind turbines as well as gear optimizations for sugar mills, vertical roller

mills and tractors. Dinner’s main interests are planetary gearboxes, tooth

contact analysis and testing.

An easy-to-use approach has been presented showing how random

gear helix slope deviations and shaft parallelism errors

due to housing errors can be considered in the calculation of KHβ. It is shown that adding up all random errors in a worstcase

scenario is overly conservative. Applying the 3-Sigma

Rule, errors may be combined in a different way such that the

resulting error covers 99.73% of all cases. The difference in the

resulting KHβ values when using this worst-case approach (in

the above example, KHβ = 1.16) vs. the more realistic statistical

approach (KHβ = 1.11) is significant when optimizing a design.

The use of the above statistical approach in consideration of

manufacturing errors in the calculation of KHβ along ISO6336-

1, Annex E or AGMA927 is recommended.

A word of caution: experience shows that when designing gear

lead modifications, or when calculating gear load distributions,

much attention should also be paid to the bearing deformation

and variation in bearing operating clearance. These effects are

not elaborated above, but are summarized in the error fpar.

Figure 1 Normal distribution of manufacturing errors, resulting error, and worst-case scenario.

Figure 1 Normal distribution of manufacturing errors, resulting error, and worst-case scenario.

Figure 2 Line load distribution in the mesh for the example — not

considering any random manufacturing errors; KHβ = 1.08.

Figure 2 Line load distribution in the mesh for the example — not

considering any random manufacturing errors; KHβ = 1.08. Figure 3 Line load distribution considering random manufacturing

errors fma = ±24.7μm (green lines); KHβ = 1.11; highest line load

occurs well within the crowned area of the face width; design

considered suitable.

Figure 3 Line load distribution considering random manufacturing

errors fma = ±24.7μm (green lines); KHβ = 1.11; highest line load

occurs well within the crowned area of the face width; design

considered suitable. Figure 4 Line load distribution considering random manufacturing errors

fma = ±41.5μm (red lines); KHβ = 1.16; highest load occurs in

the transition area between crowning and end relief; design

considered as not suitable.

Figure 4 Line load distribution considering random manufacturing errors

fma = ±41.5μm (red lines); KHβ = 1.16; highest load occurs in

the transition area between crowning and end relief; design

considered as not suitable.

Hans-Peter Dinner studied mechanical

engineering at the Swiss Federal Institute

of Technology (ETH), where during his

studies he spent time with Mercedes

Benz working on FEM of car bodies; with

Buhler in South Africa for training; and

with the National University of Singapore

for writing his thesis on FEM analysis

of medical devices. He began as an

FEM engineer, working with the leading

consultant in Switzerland on welded

structures, pressure vessels and satellite structures. Dinner later joined a

leading roller coaster design company, being responsible for all strength

verifications. He then moved on to KISSsoft AG, supporting customers in

the use of their gear software, working on gear optimization projects, and

ultimately transitioning to sales of KISSsoft products, with a focus on the

Asian market. In 2008 he started his own consultancy firm, EES KISSsoft

GmbH, sharing his time between KISSsoft support and sales in Asia and

project work. Key projects included design and testing of SCD3MW and

SCD6MW wind gearboxes, and large-bearing calculations for cranes and

wind turbines as well as gear optimizations for sugar mills, vertical roller

mills and tractors. Dinner’s main interests are planetary gearboxes, tooth

contact analysis and testing.

Hans-Peter Dinner studied mechanical

engineering at the Swiss Federal Institute

of Technology (ETH), where during his

studies he spent time with Mercedes

Benz working on FEM of car bodies; with

Buhler in South Africa for training; and

with the National University of Singapore

for writing his thesis on FEM analysis

of medical devices. He began as an

FEM engineer, working with the leading

consultant in Switzerland on welded

structures, pressure vessels and satellite structures. Dinner later joined a

leading roller coaster design company, being responsible for all strength

verifications. He then moved on to KISSsoft AG, supporting customers in

the use of their gear software, working on gear optimization projects, and

ultimately transitioning to sales of KISSsoft products, with a focus on the

Asian market. In 2008 he started his own consultancy firm, EES KISSsoft

GmbH, sharing his time between KISSsoft support and sales in Asia and

project work. Key projects included design and testing of SCD3MW and

SCD6MW wind gearboxes, and large-bearing calculations for cranes and

wind turbines as well as gear optimizations for sugar mills, vertical roller

mills and tractors. Dinner’s main interests are planetary gearboxes, tooth

contact analysis and testing.